History Buffs

![]()

Below are two documents that will be of interest to history buffs.

The first is the a 3 page listing of 9th Infantry Division infantry battalions and their assignment to brigades; included are all assigned support units along with dates of deployment in Vietnam.

The second document is a 99 page assessment of NVA and VC unit deployment within South Vietnam, 1965 through 1972. Included are descriptions of tactics and weapons used by the NVA and VC. Many photos are presented within the document. For anyone interested in a detailed history of NVA and VC tactics and armament during the Vietnam war, this is a worthwhile read.

Thanks to Paul Kasper for forwarding these documents.

![]()

9th

Infantry Division

Activated 1 Feb 1966 for service in

Vietnam and sent there Dec 1966 – Jan 1967. The division served in III and

IV CTZ, and its 2nd Brigade was the Army component of the Mobile

Riverine Force. Division headquarters was at Bear Cat Dec 1966 – Jul 1968

and Dong Tam Aug 1968 – Aug 1969. The 9th Infantry Division began

withdrawing in summer 1969, leaving its 3rd Brigade behind as a

separate unit (under

* Remained as element of separate 3rd Brigade, 9th Infantry Division.

** Formed as element of separate 3rd Brigade, 9th Infantry Division.

Notes:

Gave

up mechanized equipment and converted to infantry Sep 1968

Coy

E/50th Infantry (LRP) inactivated 1 Feb 1969 and assets used to

form Coy E/75th Infantry (Ranger).

Remained

with the separate 3rd Brigade, 9th Infantry Division

until that unit left, then served as GHQ unit, moving to the I CTZ in the

north.

ARRIVALS and DEPARTURES by BRIGADE

1st Brigade, 9th Inf Div Jan 1967 – Aug 1969

2nd Brigade, 9th Inf Div Jan 1967 – Jul 1969

3rd Brigade, 9th Inf Div Dec 1966 – Oct 1970

The DS artillery battalions were shifted. 3rd/34th, for example, was initially in DS of 3rd Brigade, but then shifted to 2nd Brigade and the Riverine role. 2nd/4th was initially in DS of 2nd Brigade, but shifted to 3rd Brigade by the time it became a separate unit summer 1969. 1st/11th is also shown as having first served in DS of 2nd Brigade.

![]()

(1965 - 1975)

Summary of NVA and VC Units as of

March 1972

Generally this summary is limited to battalions or higher. Because the list is in that format, it is sometimes difficult to work back up to subordination of all units. An asterisk indicates a border area unit (i.e., along the border) but believed to be in South Vietnam at the time. Transportation and other service-type battalions have been omitted. "RR" indicates recoilless rifle, not railroad.

I CORPS TACTICAL ZONE

Military Region 5

· 1 VC Prod Thung Dung Bn, Quang Ngai

· 107 NVA Hvy Wpns Spt Bn, Quang Ngai

· 403 NVA Sapper Bn, Quang Ngai

· 406 NVA Sapper Bn, Quang Ngai

· 409 NVA Sapper Bn, Quang Ngai

· 120 VC Mont Inf Bn, Quang Ngai (Mont = Montagnard?)

· 402 NVA Sapper Bn, Quang Ngai

· 32 NVA Recon Bn, Quang Ngai

· 404 VC Sapper Bn, Quang Nam

· 471 VC Naval Sapper Bn, Quang Nam

42 NVA Military Station

· 3rd NVA Engr Bn, Thua Thien

· 4th NVA Engr Bn, Thua Thien

· 5th NVA Engr Bn, Thua Thien

· 6th NVA Engr Bn, Thua Thien

· K6 NVA Engr Bn, Thua Thien

Nong Truong 2 NVA Inf Division

· HQ Quang Tin

· *1 VC Inf Regt [40, 60, 90 VC Bns], Quang Tin

· 21 NVA Inf Regt [4th, 5th, 6th Bns], Quang Ngai

· 31 NVA Inf Regt [1st, 2nd, 3rd Bns], Quang Tin (note that NVA Regiment 31, with a different composition, is also shown listed under B-5 Front)

· 10 NVA Sapper Bn, Quang Tin

· 12 NVA Art Bn, Quang Tin

· GK40 NVA Engr Bn, Quang Tin

Front 4

· [HQ] Quang Nam

· 38 NVA Inf Regt [7th, 8th, 9th Bns], Quang Nam

· 141 NVA Inf Regt [1st, 2nd, 3rd Bns], Quang Nam

· 577 NVA RL Bn, Quang Nam

· R20 VC Inf Bn, Quang Nam

· T89 VC Sapper Bn, Quang Nam

· 42 VC Recon Bn, Quang Nam

· 91 NVA Sapper Bn, Quang Nam

· V25 VC Inf Bn, Quang Nam

· 575 NVA Rocket Bn, Quang Nam

· 8 NVA Sapper Bn, Quang Nam

Quang Da Province

· Q82 VC LF Inf Bn, Quang Nam

· Q80 VC LF Inf Bn, Quang Nam

· 9 NVA LF Inf Bn, Quang Nam

Quang Ngai Province

· 83 VC LF Inf Bn, Quang Ngai

· 48 VC LF Inf Bn, Quang Ngai

· 40 NVA LF Inf Bn, Quang Ngai

Quang Nam Province

· 70 VC LF Inf Bn, Quang Nam

· 72 VC LF Inf Bn, Quang Tin

· 74 VC LF Cmbt Spt Bn (Mortar), Quang Tin

· D11 NVA LF Inf Bn, Quang Nam

· 14 VC LF AA-AT Bn, Quang Tin

Military Region 6

· 840 VC Inf Bn, Binh Thuan

Binh Tran 42 NVA Mil Station

· 3rd , 4th, 5th, 6th, K6 NVA Engr Bns, Thua Thien

70B Corps

· [HQ] Quang Tri

· 304B NVA Inf Division HQ Quang Tr

o 9 NVA Inf Regt [1st, 2nd, 3rd Bns], Quang Tri

o 24B NVA Inf Regt [*4th, 5th, *6th Bns], Quang Tri

o 66B NVA Inf Regt [7th, 8th, 9th Bns], Quang Tri

o 20 NVA Sapper Bn, Quang Tri

B5 Front

· [HQ] Quang Tri

· 27 NVA Inf Regt [1st, 2nd, 3rd Bns], Quang Tri

· 31 NVA Inf Regt [15th, 27th Bns], Quang Tri (also has two VC inf and two NVA sapper coys)

· 270 NVA Inf Regt [4th, 5th, 6th Bns, 6th Air Def? Bn], Quang Tri

· 84 NVA Rocket Regt [1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th RL Bns], Quang Tri

· 164 NVA Art Regt [1st, *2nd, 3rd Art Bns], Quang Tri

· 246 NVA Inf Regt[1st, 2nd, 3rd Bns], Quang Tri

· 38 NVA Art Regt [1st, 2nd, 3rd Art Bns], Quang Tri

· 33 Indep NVA Sapper Bn, Quang Tri

Tri Thien Hue Military Region

· [HQ] Thua Thien

· 4 NVA Inf Regt [K48 VC, K4C NVA Bns], Thua Thien

· 5 NVA Inf Regt [804, 810 NVA Inf, Chi Thua II VC Sapper, 32 NVA RL Bns], Thua Thien

· 6 NVA Inf Regt [800, 802, 806 NVA Inf, 12 NVA Sapper, 35 NVA RL Bns], Thua Thien

· K3 NVA Sapper Bn, Thua Thien

· K44 NVA Engr Bn, Thua Thien

· 11A NVA Recon Bn, Thua Thien

7th NVA Front

· [HQ] Quang Tri

· *324B NVA Inf Division HQ, Quang Tri

o 803 NVA Inf Regt [1st, 2nd, 3rd Bns], Thua Thien

o 29 NVA Inf Regt [7th, 8th, 9th Bns], Thua Thien

o 812 NVA Inf Regt [4th, 5th, 6th Bns], Quang Tri

Quang Tri Province

· K34 NVA Rocket Bn, Quang Tri

· 10 NVA Sapper Bn, Thua Thien

· 814 NVA Inf Bn, Quang Tri

· 808 NVA Inf Bn, Quang Tri

Thua Thien Province

· Phu Loc VC LF Inf Bn, Thua Thien

NVA Sapper Combat Group

· 126 Naval Sapper Regt, Quang Tri (battalion-sized?)

Quang Binh Province

· 49 NVA LF Inf Bn, Quang Tri

320 NVA Inf Division

· 52B NVA Inf Regt [HQ only], Quang Tri

[There were also 63 VC and 3 NVA companies in ARVN MR 1: 57 maneuver and 6 combat support VC, 2 maneuver and 1 combat support NVA.] - See Below*contains identified companies.

II CORPS TACTICAL ZONE

Military Region 5

· 407 VC Sapper Bn, Khanh Hoa

Nong Truong

· 3 NVA Inf Division

o HQ Binh Dinh

o 12 NVA Inf Regt [4th, 5th, 6th Bns]

o 2 NVA Inf Regt [1st, 2nd, 3rd Inf, 4th Sapper, 5th Art Bns], Binh Dinh

o 90 NVA Engr Bn, Binh Dinh

o 200 NVA Air Def Bn, Binh Dinh

Binh Dinh Province

· 50 VC LF Inf Bn, Binh Dinh

· E 210 VC LF Inf Bn, Binh Dinh

· 405 VC LF Sapper Bn, Binh Dinh

· 8 NVA LF Inf Bn, Binh Dinh

Khanh Hoa Province

· K12 NVA LF Inf Bn, Khanh Hoa

· Khanh Hoa VC LF Sapper Bn, Khanh Hoa

Phu Yen Province

· 96 VC LF Inf Bn, Phu Yen

· K13 NVA LF Inf Bn, Phu Yen

· K14 VC LF Sapper Bn, Phu Yen

· 9 NVA LF Inf Bn, Phu Yen

Military Region 6

· 130 NVA Art Bn, Binh Thuan

· A16 NVA Sapper Bn, Tuyen Duc

· 186 VC Inf Bn, Binh Thuan

· 240 NVA Inf Bn, Binh Thuan

Binh Thuan Province

· 481 VC LF Inf Bn, Binh Thuan

· 482 VC LF Inf Bn, Binh Thuan

Tuyen Duc Province

· 810 VC LF Inf Bn, Tuyen Duc

Military Region 10

Quang Duc Province

· D251 VC LF Inf Bn Quang Duc

B3 NVA Front

· [HQ] Kontum

· 24 NVA Inf Regt [4th, 5th, 6th Bns], Pleiku

· 66 NVA Inf Regt [*7th, 8th, *9th Bns], Kontum (from Cambodia)

· 95B NVA Inf Regt [K1, K63, K394 Bns], Pleiku

· 28 NVA Inf Regt [K1, K2, K3 Bns], Kontum

· 40 NVA Art Regt [K16, K33, K40 NVA Art, K32 NVA (120mm) Mortar, K30 NVA Air Def Bns], Kontum

· K25 NVA Engr Bn, Kontum

· K37 NVA Sapper Bn, Kontum

· *K20 NVA Sapper Bn, Kontum (from Cambodia)

· 631 NVA Inf Bn, Pleiku

· K28 NVA Recon Bn, Kontum

· K80 NVA Sapper Bn, Kontum

· K27 NVA Guard Bn, Kontum

Darlac Province

· E 301 VC LF Inf Bn, Darlac

· 401 VC LF Sapper Bn, Darlac

Kontum Province

· 304 VC LF Inf Bn, Kontum

· 406 VC LF Sapper Bn, Kontum

Gia Lai Province

· 408 VC LF Sapper Bn, Pleiku

· X67 VC LF Inf Bn, Pleiku

· K2 NVA LF Inf Bn, Binh Dinh

· 450 VC LF Sapper Bn, Binh Dinh

· X45 VC Inf Bn, Pleiku

[There were also 93 VC and 1 NVA companies in ARVN MR 2: 87 maneuver and 6 combat support VC, 1 maneuver NVA.]

III CORPS TACTICAL ZONE

COSVN

· [HQ] Tay Ninh

· [Forward HQ], Binh Duong

· 180 VC Security Regt [O1, *O2 VC Sec Bns], Tay Ninh

· 46 VC Recon Bn, Tay Ninh

· 190 VC Sec Guard Bn, Tay Ninh

· A66 VC Strat Recon Bn, Tay Ninh

69 VC Artillery Division

· [HQ] Tay Ninh

· 96 NVA Art Regt [K3 and K4 NVA , K5 VC Art Bns]; Binh Long (K3 and K5), Tay Ninh (HQ and K4)

· 208B NVA Rkt Regt (1, 2 NVA RL, 22 NVA Art Bns), Tay Ninh

· 56 VC Air Def Bn, Tay Ninh

· 58 VC Art Bn (Mortar), Tay Ninh

Cong Truong 5 VC Inf Division

· HQ Phuoc Long

· 275 VC Inf Regt [1st, 3rd Bns], Phuoc Long

· 174 NVA Inf Regt [1st, 2nd, 3rd Bns], Tay Ninh

· *6 VC Inf Regt [7th, *8th, *9th Bns], Binh Long

· 22 NVA Art Bn, Binh Long

· 24 NVA Air Def Bn, Binh Long

· *27 VC Recon Bn, Binh Long

· *28 VC Sapper Bn, Binh Long

Cong Truong 7 NVA Inf Division

· HQ Tay Ninh

· 141 NVA Inf Regt [1st, 2nd, 3rd Bns], Tay Ninh

· 165 NVA Inf Regt [1st, 2nd, 3rd Bns], Tay Ninh

· 209 NVA Inf Regt [K4, K5, K6 Bns], Tay Ninh

· K22 NVA Art Bn, Tay Ninh

· 24 NVA Air Def Bn, Tay Ninh (the duplication of the designation in CT 5 VC Inf Div is in the original document)

· 28 NVA Engr Bn, Tay Ninh

· 95 NVA Recon Sapper Bn, Tay Ninh

Cong Truong 9 VC Inf Division

· HQ Tay Ninh

· 271 VC Inf Regt [1st, *2nd, 3rd, 4th Bns], Tay Ninh

· *272 VC Inf Regt [1st, *2nd, *3rd Bns], Tay Ninh

· 95C NVA Inf Regt [4th, 5th, 6th Bns], Tay Ninh

· 22 VC Art Bn, Tay Ninh

· 24 VC Air Def Bn, Binh Long

· T28 VC Recon Bn, Tay Ninh

Tay Ninh Province

· D1 VC LF Inf Bn, Tay Ninh

· D14 VC LF Inf Bn, Tay Ninh

Ba Ria SR

· D2 VC Inf Bn, Bien Hoa

· 8 VC Swimmer Sapper Bn, Bien Hoa

· Doan 10 VC Sapper Bn, Bien Hoa

· D445 VC LF Inf Bn, Long Khanh

· 6 NVA Sapper Bn, Long Khanh

· 74 NVA Rkt Regt [1st, 2nd, 3rd RL Bns]: Bien Hoa (HQ, 1st and 2nd) and Long Khanh (3rd)

· 274 VC Inf Regt [1st, 2nd, 3rd Bns]: Bien Hoa (HQ and 3rd) and Long Khanh (1st and 2nd)

· 33 NVA Inf Regt [K1, K2, K3 Bns]: Phuoc Tuy (HQ and K3), Long Khanh (K1), Binh Tuy (K2)

Thu Bien SR

· 2 VC Inf Bn, Phuoc Long

· D1 VC Sapper Bn, Bien Hoa

· K1 VC Inf Bn, Binh Duong

· K2 NVA Inf Bn, Bien Hoa

· D2 VC Inf Bn, Long Khanh

· K4 VC Inf Bn, Binh Duong

Sub Region 1

· 101 NVA Inf Regt [1st, 2nd, 3rd Bns]: Binh Long (HQ), Binh Duong (1st), Hau Nghia (2nd), Tay Ninh (3rd)

· Gia Dinh 4 NVA Sapper Bn, Gia Dinh

· 268 VC Sapper Bn, Hau Nghia

· 89 VC Art Bn, Binh Duong

Long An Sub Region

· 6 VC Inf Bn, Long An

· 12 VC Sapper/Recon Bn, Hau Nghia

· 267 VC Inf Bn, Hau Nghia

· 1696 VC Inf Bn, Hau Nghia

· 211 NVA Sapper Bn, Long An

· 506 VC Inf Bn, Long An

· Dong Phu NVA Inf Bn, Long An

· An My NVA Inf Bn (shows grid reference, no place name)

· 520 VC Inf Bn (shows grid reference, no place name strength shown as 20)

Military Region 10

· G45 NVA Inf Bn, Phuoc Long

Binh Long Province

· 368 VC LF Inf Bn, Binh Long

Phuoc Long Province

· D168 VC LF Inf Bn, Phuoc Long

NT 1 NVA Inf Division

· 25 NVA Engr Bn, Tay Ninh

· 24 NVA AA Bn, Tay Ninh (another near duplicate designation in the original document, although this is shown as AA rather than AD)

Sapper Command

· [HQ] Nov 1965 Tay Ninh

· 7 NVA Sapper Bn, Tay Ninh

· 8 NVA Sapper Bn, Tay Ninh

· 9 NVA Sapper Bn, Binh Duong

· 10 NVA Sapper Bn, Tay Ninh

· (VC) *Recon Bn, Tay Ninh

· 13 NVA Sapper Bn, Binh Duong

· D16 NVA Sapper Bn, Tay Ninh

· D14 NVA Sapper Bn, unknown

[There were also 44 VC and 1 NVA companies in ARVN MR 3, all maneuver.]

IV CORPS TACTICAL ZONE

Sapper Command

Military Region 2

· 88 NVA Inf Regt [K7, K8, K9 Inf, K10 Sapper Bns]: Dinh Tuong (HQ, K1, K2), Kien Tuong (K9), Kien Phong (K10)

· DT1 VC Inf Regt [261A, 261B Inf, 269B Sapper Bns], Dinh Tuong

· *295 VC Inf Bn, Kien Phong

· Binh Duc VC Art Bn, Dinh Tuong

· 341 VC Sapper Bn, Dinh Tuong

· 267B VC Sapper Bn, Dinh Tuong

· 271 VC Inf Bn, Kien Tuong

An Gian Province

· *511 VC LF Inf Bn, Chau Doc

· 512 VC LF Inf Bn, Chau Doc

· 510 VC LF Inf Bn, Chau Doc

Ben Tre Province

· 516A VC LF Inf Bn, Kien Hoa

· 516B VC LF Inf Bn, Kien Hoa

· 516 VC LF Inf Bn, Kien Hoa

· 263 VC LF Inf Bn, Kien Hoa

Go Cong Province

· 514A VC LF Inf Bn, Go Cong

Kien Phong Province

· 502 VC LF Inf Bn, Kien Phong

Kien Tuong Province

· 504 VC LF Inf Bn, Kien Tuong

My Tho Province

· 514C VC LF Inf Bn, Dinh Tuong

· 207 VC LF Sapper Bn, Dinh Tuong

Military Region 3

· D1 VC Inf Regt [309th, 303rd Bns], Chuong Thien

· D2 VC Inf Regt [Z7th, Z8th, Z9th Inf, Z10th Sapper Bns]: Kien Giang (HQ, 29th, 210th), An Xuyen (27th), Chuong Thien (28th)

· D3 VC Inf Regt [306th, 312th Bns]: Vinh Binh (HQ and 306th), Vinh Long (312th)

· 95A NVA Inf Regt [27th, 28th, 29th NVA Inf 23rd VC Sapper Bns]: Kien Giang (HQ, 23rd), An Xuyen (27th—29th)

· 188 NVA Inf Regt [Z4, Z5, Z6 Inf, T28 Sapper Bns], Kien Giang

· 2311 VC Art Bn, Chuong Thien

· TN3173 VC Inf Bn, Kien Giang

· 301 VC Sapper/Engr Bn, Kien Giang

· 2315 VC Art Bn, An Xuyen

· 962 VC Inf Bn, An Xuyen

· 307 VC Inf Bn, Kien Giang

Ca Mau Province

· U Minh 2 VC LF Inf Bn, An Xuyen

Can Tho Province

· Tay Do I VC LF Inf Bn, Chuong Thien

· Tay Do II VC LF Inf Bn, Phong Dinh

Rach Gia Province

· U Minh 10 VC LF Inf Bn, Chuong Thien

Soc Trang Province

· D764 VC LF Inf Bn, Chuong Thien

Tra Vinh Province

· 501 VC LF Inf Bn, Vinh Binh

Vinh Long Province

· O857 VC LF Inf Bn, Kien Hoa

Phuoc Long Group

· 410 VC Inf Bn, Kien Giang

[There were also 107 VC companies in ARVN MR 4: 99 maneuver and 8 combat support.]

ATTACHMENT C. Identified Companies.

|

|

|

|

|

All of these are VC unless explicitly labeled NVA. Mar 1972 location province is shown after the unit in two cases: the unit is not subordinated to a province, or it is shown located in a province other than that implied by its subordination to a province or district.

I CORPS TACTICAL ZONE

7th Military District

Front 4

Quang Tri Province

Thua Thien Province

Quang Da Province

Quang Ngai Province

Quang Nan Province

II CORPS TACTICAL ZONE

Military Region 6

B3 Front

Ninh Thuan Province

Lam Dong Province

Binh Thuan Province

Tuyen Duc Province

Darlak Province

Kontum Province

Gia Lai Province

Binh Dinh Province

Khanh Hoa Province

Phu Yen Province

III CORPS TACTICAL ZONE

Tay Ninh Province

Ba Ria Special Region

Thu Bien Special Region

Sub Region 1

Long An Subregion

Phuoc Long Province

Binh Tuy Province

IV CORPS TACTICAL ZONE

Military Region 2

An Giang Province

Ben Tre Province

Go Cong Province

Kien Phong Province

Kien Tuong Province

My Tho Province

Ca Mau Province

Can Tho Province

Rach Gia Province

Soc Trang Province

Tra Vinh Province

Vinh Long Province

NVA & VC Base Camps

GENERAL

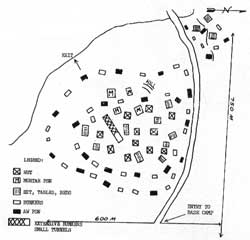

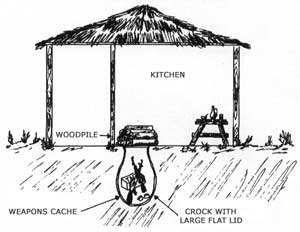

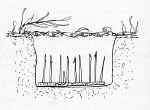

Fortified base camps were the pivots of Viet Cong (VC) military operations and, it was believed, if denied their use, the VC movement would wither. Local force units tended to place reliance on numerous small base camps dispersed throughout their area of operations and each unit attempted to maintain at least one elaborately fortified refuge. The larger local force units normally constructed a tunnel complex which housed their hospital and headquarters. The camps were usually extensively booby trapped and protected by punji stakes, mines and spike traps. Main Force base camps, on the other hand, were usually not so well guarded by mines; they were however, larger and frequently included training facilities, such as rifle ranges and classrooms. Main Force units invariably had pre-stocked base camps throughout their area of operations and often shifted their forces as the tactical situation dictated, either for offensive or defensive reasons.

Figure 1

Years of labor and an immense amount of material went into building a complex network of base camps throughout the country. It was this network which sustained irregular operations. A semi-guerrilla army, such as that of the VC, could no more survive without its base camps than a conventional army could survive when cut off from its main bases. However remote and concealed, the base camps could not be easily moved or hidden indefinitely. To find and destroy these camps was a prime objective of the allied military effort.

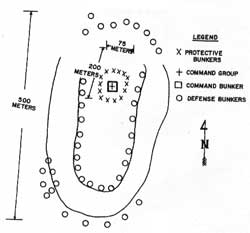

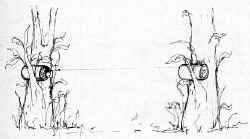

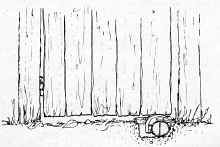

Defended base camps presented a formidable obstacle to the attacker. They were normally somewhat circular in form with an outer rim of bunkers, automatic weapons firing positions, alarm systems and foxholes. Within the circle there was a complete system of command bunkers, kitchens and living quarters constructed above the ground from a wide variety of materials. (Figs. 1, 2 and 3 illustrate the various types of VC base camps which were encountered by tactical units in South Vietnam).

Figure 2

The exact shape of the camp varied in order to take maximum advantage of natural terrain features for protection and to restrict attack on the camp to one or two avenues. Some of the camps, particularly those used only for training or way stations, had minimum defensive works. However, in all cases, the enemy was prepared to defend his camp against a ground attack. Even though natural terrain features may have caused a given camp to resemble a cul-de-sac there was at least one prepared exit or escape route opposite the anticipated direction(s) of attack. Tunnels connected the bunkers and firing positions, enabling the defenders to move from one point to another. This technique enhanced the effect of their firepower and gave them a significant advantage over the attacker. An unfordable river often paralleled one flank of a typical camp while open paddy land bordered the other.

The apparent lack of escape routes made the position appear like an ideal target for ground attack. However, until bombardment had removed most of the foliage, any maneuver into these areas on the ground was a complex problem. One local force squad had been known to withstand the assault of two US Army infantry companies, and a VC sniper or two, firing from within a mined camp, could inflict numerous casualties on the attacking force.

LOCATION AND DETECTION OF BASE CAMPS

The 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division (US), made a study to determine if patterns existed for the establishment of enemy base camps and defensive fortifications. It was found early in the operation that the enemy invariably established his bases in the upper reaches of draws where water was available and dense foliage precluded aerial observation. Fortifications were found on the "fingers" covering the base camps and were mutually supporting. A comparison with information obtained from other sources such as agent reports, trail studies, etc., indicated that a pattern did exist and that potential base areas and bunkered positions could be predicted with reasonable accuracy. Based on this finding, information obtained from the Combined Intelligence Center, Vietnam (CICV), photos, Red Haze, visual reconnaissance and special agent reports was placed on overlays and the density of activity plotted. The plot was then transferred to maps using the color red to represent probable base camp locations. A careful study of surrounding terrain was then made to determine likely defensive positions and these were entered in blue on the map. Thus, commanders were presented with a clear indication of the most likely areas which would be defended. This method of identifying probable base camps and defensive positions proved to be relatively accurate.

During OPERATION MAKALAPA, the 25th Infantry Division (US) found that VC base camps were normally located along streams and canals and that extensive bunker complexes were built into the banks. Bunkers were usually constructed of a combination of mud, logs and cement. The bunkers presented a low silhouette and had extensive lanes of fire along the main avenue(s) of approach. Excellent camouflage negated the effectiveness of allied aerial and ground observation.

In OPERATION WHEELER, the 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division (US) found that "People Sniffer" missions effectively produced intelligence in areas of heavy vegetation where visual reconnaissance was ineffective. These missions were also invaluable in verifying agent reports as well as specifically locating enemy units, hospitals or storage areas as revealed by detainees or captured documents.

The After Action Report of the 25th Infantry Division (US) for OPERATION JUNCTION CITY, reflected that of the sixteen base camps discovered, two wore considered to be regimental size, ten battalion size and four company size or smaller. All base camps were located 200 meters or closer to a stream or other source of water. Each camp was encircled by a bunker system with interconnecting trench systems. The defensive positions showed evidence of careful planning of fields of fire and were well camouflaged and expertly organized. Enemy claymore mine positions were marked on the enemy side of a tree, usually with a single strip of white cloth or an "X"' cut into the tree.

Figure 3

The 3rd Brigade, 1st Infantry Division (US) reported, after the completion of OPERATION JUNCTION CITY, that most base camps were located near streams or roads. It appeared that the plan was to locate all installations close to transportation routes. This Brigade made the same comment in their After Action Report for OPERATION BATTLE CREEK.

The 3rd Battalion, 22nd Infantry, 4th Division (US) After Action Report for OPERATION BREMERTON, which was conducted in the Rung Sat Special Zone, reflected that the most likely base camps in that area existed on the high ground. Therefore, caution had to be exercised when entering dry ground from the swamps. Also, all base camps encountered were within 150 meters of some type of waterway. Further, these camps, without exception, were well concealed and effectively bunkered. Similarity of these base camps enabled units to plan their method of approach to minimize friendly casualties.

In the conduct of OPERATION BENTON by the 196th Light Infantry Brigade (US), it was noted that in almost all cases the enemy installations were within 1000 meters of a valley or actually in the valley. This indicated that in this area, the VC avoided the rugged and more formidable higher elevations.

The 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division (US) found in OPERATION HOOD RIVER, that the VC continued to utilize mutually supporting draws, each characterized by a water supply, dense foliage and fortified positions guarding accesses to base camp areas. This same unit noted in their After Action Report for OPERATION BENTON that the VC guarded his base camps with local forces who wore well trained and very capable of executing all aspects of guerrilla warfare.

Following OPERATION YELLOWSTONE, the 3rd Squadron, 17th Cavalry (-) (US) reported that sightings of previously unlocated base camps were reported daily. As each sub-area was searched in detail, large bunker complexes were located along every large stream in the jungle area. Enemy lines of communication interlacing the fortified base camps were found and plotted. Many of the base camps were vacant but a large percentage proved to be occupied and well defended.

The After Action Report of the 1st Brigade, 25th Infantry Division (US) for OPERATION LANIKAI reflected that during this operation VC base camps were normally found along stream beds adjacent to built-up areas or in the midst of occupied villages. Bunkers were found in most homes, astride or strung along roads and dikes and in the corners of hedge rows. Pagodas were normally VC meeting places and were often protected by bunker complexes.

The use of the "Open Arms" program to obtain intelligence of specific areas and for guides to areas could be very effective. During OPERATION DAN TAM 81, conducted by the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, the exact locations of VC base camps were revealed by a Hoi Chanh.

The 1st Battalion, 18th Infantry, 1st Infantry Division (US) reported upon completion of OPERATION BATON ROUGE that whenever a unit moved into an area where there were indications that much wood had been cut, the unit expected to find a base camp within 200 to 500 meters of the cutting area. (Note: VC regulations prescribed that wood cutting must be done at least one hour's walking time from such facilities.) Upon completion of OPERATION LEXINGTON III, this same unit reported that base camps and facilities were generally found near streams, indicating the need for easy accessibility in the type of terrain encountered in the area.

During OPERATIONS MANCHESTER, UNIONTOWN/STRIKE and UNIONTOWN I, the 199th Brigades 503rd Chemical Detachment conducted twelve "People Sniffer" missions during the period 17 December 1967 to 13 January 1968, identifying 94 hot spots of probable enemy activities. The "People Sniffers" enjoyed several successes by identifying VC base camps and supplementing other intelligence means in locating areas of enemy activity.

The After Action Report of the 199th Light Infantry Brigade for OPERATIONS MANCHESTER, UNIONTOWN/STRIKE and UNIONTOWN I contained the comment that the humane and considerate treatment of Hoi Chanhs reaped high dividends, saving countless man-hours of operational time. Once the confidence of these returnees was gained and sincere concern for their well being was established, they willingly provided information leading to identification and destruction of Viet Cong forces or their base camps.

For a long time it was thought that because of their superior knowledge of these areas, the Viet Cong habitually established base areas deep in the interior. Operations conducted by the 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division tended to disprove this belief. Apparently the Viet Cong did not regularly inhabit the interior of dense jungle areas unless they were accessible by trail. Instead, they operated from bases within two or three kilometers of the jungle periphery.

Upon completion of OPERATION JUNCTION CITY, the 196th Light Infantry Brigade reported that defoliation flights cleared away brush and effectively revealed the enemy's base camps and supply routes.

The 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne) reported that the questions most frequently asked local VC PWs and ralliers, especially Hoi Chanhs, pertained to the location of their base camps and AOs. The 5th SFG found that the two frequently used methods of map study and aerial observation were unsuccessful. Most PWs and Hoi Chanhs did not know direction, could not read a map and, when they were taken aloft for Visual Reconnaissance (VR), it was usually their first flight so they could not associate what they saw from the air with what they saw on the ground. However, most of these people would not admit that they were unable to read a map, tell direction or do a terrain analysis from the air. As a consequence, they usually replied in the affirmative when questions were asked. When detainees were re-interrogated using the same techniques, the information received in the second interrogation frequently differed from the first interrogation. One method of interrogation which proved successful was based on direct terrain orientation questions by the interrogator. First the detainee was asked the direction of the sun when he last left the base camp. He was then asked how long it took him to walk to the point where he Chieu Hoi'd or was captured. Judging from the type of terrain and health of the detainee the distance to the camp could generally be determined. The subject was then asked to enumerate significant terrain features he saw on each day of his journey, i.e., open areas, rubber lots, hills, rice paddies, swamps, etc. As the subject spoke and his memory was jogged, the interrogator found these terrain features on a current map and gradually plotted the subject's route and finally identified the area in which the base camp was located.

METHODS OF DESTROYING OR RENDERING BASE CAMPS UNTENABLE

The 1st Australian Task Force used tactical airstrikes, immediate and preplanned, against occupied enemy base camps during OPERATION INGHAM. Assessment of damage revealed that one strike was on target and destroyed two underground rooms, collapsed 60 yards of tunnel and blew in several weapons pits. One strike was not assessed as the camp was not revisited. The Task Force also reported that airstrikes were directed against the camps to force the enemy out of occupied camps during OPERATION PADDINGTON.

The 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division's method of rendering base camps untenable, as reported in their After Action Report for OPERATION MALHEUR, was to contaminate them from the air using CS. The CS concentration remained effective for a period of from four to six weeks.

During OPERATION DALLAS, the 2/2 Infantry (Mech) conducted jungle clearing operations in the Vinh Loi Woods with tank dozers and Rome Plows. During jungle clearing, when contact was made which indicated the presence of a VC base camp, the mechanized elements developed the situation by deploying laterally while directing supporting air and artillery fires into the suspected base camp. The jungle clearing vehicles immediately began clearing a swath completely around the base camp. When the circle was completed, additional swaths were progressively cleared into the center of the camp. The configuration of the cleared jungle took on the appearance of a spoked wheel superimposed on the base camp. After occupation and security of the base camp by mechanized elements, the camp would be systematically destroyed by dozers. The 2nd Brigade, 1st Infantry Division also reported the use of both Rome Plows and demolitions to destroy enemy base camps during this same operation.

The 4th Infantry Division utilized tactical air to destroy bunkers during OPERATION FRANCIS MARION. Battle damage assessment (BDA) indicated two bunkers destroyed and one or two bunkers damaged severely, depending upon point of impact. Eight-inch artillery did not affect the bunkers unless there was a direct hit and then only the bunker receiving a direct hit was destroyed. The 3rd Brigade, 4th Infantry Division reported after OPERATION NISQUALLY that enemy base camps were destroyed by burning but that during the dry season caution had to be exercised to prevent the fire from spreading to the adjacent jungle.

The 1st Infantry Division's tactic for destroying VC base camps during OPERATION TUCSON was that of backing off, destroying them with air and artillery, and then sweeping through the base camp with troops. During OPERATION CEDAR FALLS, this same division found that a dozer team of two tank dozers and six bulldozers was very effective, particularly when working in a joint effort with infantry. The infantry provided the security and the dozers destroyed the base camps and fortifications.

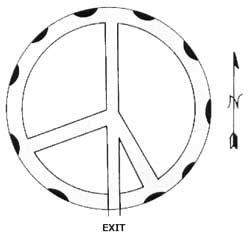

Figure 4: Base camp circular bunker

During OPERATION ATTLEBORO, elements of the 2nd Brigade, 1st Infantry Division discovered nine base camps, all of which had the same type fortifications. These ranged from open trenches and foxholes to bunkers with overhead cover. The largest base camp had fifty bunkers with overhead cover. Overhead cover consisted of logs with a layer of dirt. Destruction was difficult. At times units would physically remove the overhead cover and fill in the holes. The most elaborate was a circular bunker (See Fig 4). The bunker was 50 meters in diameter and the trench was 5 feet deep and 2 feet wide. 10 dugout holes in the trench were large enough for one man's protection against artillery. 6 claymores were wired and in the trench ready for ground emplacement. Control to fire the claymores was located at the southern exit. When demolitions were available they were used to destroy the bunkers. The primary means, however, of destroying the enemy installations was to call for air and artillery after evacuating the area.

SUMMARY OF SALIENT LESSONS LEARNED WITH RESPECT TO VC BASE CAMPS.

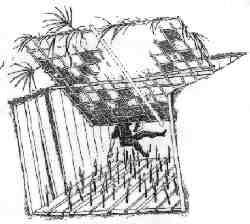

Allied Operations Against Tunnel Complexes

The use of tunnels by the VC as hiding places, caches for food and weapons, headquarter complexes and protection against air strikes and artillery fire was a characteristic of the Vietnam war. The 'fortified village', usually underlaid by an extensive tunnel system containing conference, storage and hiding rooms as well as interconnected fighting points had also been frequently encountered. However, as operations progressed into the war zones subsequent to January 1966, an even more extensive type of tunnel complex had begun to be encountered which combined underground security of personnel and supplies with an integrated, tactically located defensive system of fighting bunkers.

US tunnel rat prepares to enter

enemy tunnel system

The tunnel/bunker complexes encountered in the war zones were obviously the result of many years of labour, some in all probability having been initiated as early as WWII, with extension and improvement continuing throughout the war against the French and up until the time of their discovery by the US troops. These complexes presented a formidable and dangerous obstacle to operations that had to be dealt with in a systematic, careful and professional manner. Additionally, they were an outstanding source of intelligence, as evidenced by the several tons of documents found during the clearing of the Saigon-Cholon-Gia Dinh headquarters complex in Operation Crimp, January 1966.

Tunnel Characteristics

The first characteristic of a tunnel complex is normally superb camouflage.

Entrances and exits are concealed, bunkers are camouflaged and even within the

tunnel complex itself, side tunnels are concealed, hidden trapdoors are

prevalent, and dead-end tunnels are utilised to confuse the attacker. In many

instances the first indication of a tunnel complex was fire received from a

concealed bunker that might otherwise have gone undetected. Spoil from the

tunnel system was normally distributed over a wide area.

Trapdoors were utilised extensively, both at entrances and exits and inside the tunnel complex itself, concealing side tunnels and intermediate sections of the main tunnel. In many cases a trapdoor would lead to a short change-of-direction or change-of-level tunnel, followed by a second trapdoor, a second change-of-direction and a third trapdoor opening again into the main tunnel.

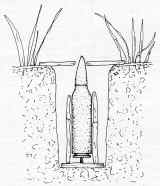

Trapdoors were of several types; concrete covered by dirt, hard packed dirt reinforced by wire, or a 'basin' type consisting of a frame filled with dirt. This latter type was particularly difficult to locate in that probing would not reveal the presence of the trapdoor unless the outer frame was actually struck by the probe. Trapdoors covering entrances were generally a minimum of 100 meters apart. Booby traps were used extensively, both inside and outside entrance and exit trapdoors. Grenades were frequently placed in trees adjacent to the exit, with an activation wire to be pulled by a person underneath the trapdoor or by movement of the trapdoor itself. Typical trapdoor configurations are shown below;

Tunnel complexes found in the War Zones were generally more extensive and better constructed than those found in other areas. In some cases these complexes were multileveled, with storage and hiding rooms generally found on the lower levels. Entrance was often gained through concealed trapdoors and secondary tunnels. In the deeper complexes, foxholes were dug at intervals to provide water drainage. These were sometimes booby-trapped as well as containing punji-stakes for the unwary attacker.

Although no two tunnel systems were exactly alike, a complex searched by 1st Battalion, RAR, during Operation Crimp may serve as a good example. The complex had the following characteristics;

Another tunnel characteristic of note was the use of air or water locks that acted as 'firewalls', preventing blast, fragments or gas from passing from one section of the tunnel complex to another. Use of these 'firewalls' is illustrated below;

Recognition of their cellular nature was important for understanding these tunnel complexes. Prisoner interrogation indicated that many tunnel complexes were interconnected, but the interconnecting tunnels, concealed by trapdoors or blocked by 3 to 4-feet of dirt, were known only to selected persons and were used only in emergencies. Indications also pointed to interconnections of some length, e.g. 5 to 7-kilometers, through which relatively large bodies of men could be transferred from one area to another, especially from one 'fighting' complex to another.

The 'fighting' complexes terminated in well-constructed bunkers, in many cases covering likely landing zones in a war zone or base area. Bunker construction is illustrated below with examples uncovered by 1st Battalion, 503rd Airborne, during Operation Crimp;

|

|

|

Bunker raised three feet with four firing ports |

|

|

|

Bunker raised approximately one foot with one firing port |

|

|

|

Command Bunker |

Integration of these bunkers into a 'fighting' position is illustrated by the following diagram apparently used as a guide for VC construction in the CRIMP area;

|

|

The following experience of the 1st Infantry Division in the Di An and Cu Chi area is representative of tunnel operations; Tunnel Exploitation and Destruction · The area in the immediate vicinity of the tunnel was secured and defended by a 360-degree perimeter to protect the tunnel team · The entrance to the tunnel was carefully examined for mines and booby traps · Two members of the team entered the tunnel with wire communications to the surface · The team worked it's way through the tunnel, probing with bayonets for booby traps and mines and looking for hidden entrances, food and arms caches, water locks and air vents · As the team moved through the tunnel, compass headings and distances traversed were called to the surface where a team member mapped the tunnel · Captured arms and food items were turned over to the unit employing the team |

As other entrances were discovered and plotted, they were marked in such a way as to indicate if the VC used them after discovery, but before destruction could be accomplished. In many cases tunnels were too extensive to be exploited and destroyed in the same day and the VC mined entrances and approaches during the night after the tunnel team departed.

Upon completion of exploitation, forty pound cratering charges were placed fifteen to twenty meters from all known tunnel entrances and, where extensive tunnel complexes existed, ten pound bags of CS-1 Riot Control Agent were placed at intervals down the tunnel at sharp turns and intersections and tied into the main charge. Where sufficient detonating cord was not on hand to tie-in all bags of CS-1 to the main charge, bags of CS-1 were dispersed in the tunnel by detonation with a defused M-26 fragmentation grenade fused with a non-electric cap and a length of time fuse. Sharp turns in the tunnel protected the demolitions man from the grenade blast, if the detonation occurred before he exited the tunnel.

Tunnel Flushing and Denial

The infantryman discovering a spider hole or tunnel entrance during intensive

combat lobs an M-25 CS 'baseball type' grenade in the hole, followed by a

fragmentation grenade. The bursting of the CS gas grenade places an

instantaneous cloud of CS in the tunnel and the fragmentation grenade blows the

CS through a section of the tunnel while killing any VC near the entrance.

The low level contamination resulting from this method would serve only to discourage rather than prevent future VC use of that tunnel entrance.

Hasty Tunnel Flushing and Denial

In some areas the combat situation would permit a hasty search for hidden tunnel entrances but either lack of time or VC occupation of the tunnel would not permit exploitation by the tunnel team as described above (Tunnel Exploitation and Destruction).

In this case the Mity Mite Portable Blower could be employed to flush the VC from the tunnels burning CS Riot Control Agent grenades (M-7A2). In addition, the smoke from the grenades would, in most cases, assist in locating hidden entrances and air vents.

After flushing with CS grenades, powdered CS-1 could be blown into tunnel entrances to deny the tunnel to the VC for limited periods of time. In either case, these methods were only effective up to the first 'firewall' in the tunnel.

Representative Equipment List;

Protective mask; TA-1 telephone; one half mile field wire on 'doughnut' roll; compass (x2); sealed beam 12-volt flashlight (x2); small caliber pistol (x2); probing rods (12-inch and 36-inch); bayonet (x2); M7A2 CS grenades (x12); powdered CS (as required); coloured smoke grenades (x4); insect repellent and spray (4 cans); entrenching tool.

Small caliber pistols or pistols with silencers were the weapons of choice in tunnels, since larger caliber weapons without silencers had been known to collapse sections of the tunnel when fired and/or damage eardrums.

Careful mapping of the tunnel complex often revealed other hidden entrances as well as the location of adjacent tunnel complexes and underground defensive systems. Constant communication between the tunnel team and the surface was thus essential to facilitate tunnel mapping and exploitation.

Colored smoke grenades were often used to mark the location of additional entrances as they were found. In the dense jungle it was often difficult to locate the position of these entrances without smoke.

Dangers

Dangers inherent in the above operations fell into the following categories and had to be taken into account by all personnel connected with these operations;

· Mines and booby traps in the tunnel entrance/exit area

· Punji pits inside entrances

· Presence of small but dangerous concentrations of carbon monoxide, produced by burning-type smoke grenades after tunnels were smoked. Protective masks would prevent inhalation of smoke particles, which were dangerous only in very high concentrations, but would not protect against carbon monoxide

· Possible shortage of oxygen as in any confined or poorly ventilated space

· VC still in the tunnel who posed a danger to friendly personnel both above and below ground

Conclusions

A trained tunnel exploitation and denial team was essential to the expeditious and thorough exploitation and denial of VC tunnels since untrained personnel may have missed hidden tunnel entrances and caches, taken unnecessary casualties from concealed mines and booby traps and may not have adequately denied the tunnel to future VC use. To facilitate this, teams were trained, equipped and maintained in a ready status to provide immediate assistance when tunnels were discovered.

Tunnels were frequently found to be outstanding sources of intelligence and would therefore be exploited to the maximum extent possible. However, since tunnel complexes were carefully concealed, often extensive, and well camouflaged, search and destroy operations had to provide adequate time for a thorough search of the area to locate all tunnels. Complete exploitation and destruction of tunnel complexes was very time consuming and operational plans had to be made accordingly in order to ensure success.

The presence of a tunnel complex within or near an area of operations posed a continuing threat to all personnel in the area and no area containing tunnel complexes could ever be considered completely cleared.

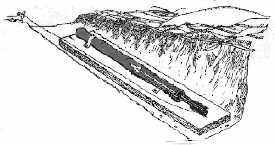

NVA & VC Supply Caches

GENERAL

The combat experience of allied forces confirmed that supply caches were the lifeblood of the enemy's offensives. Without them, the Viet Cong's (VC) capability to sustain operations was seriously impaired. Cache destruction had an adverse affect upon the morale of the enemy individuals and units, and had a significant military impact on his operational plans and logistical support. Loss of medical supplies further compounded the VC's problem of maintaining unit effectiveness and conducting propaganda and recruitment operations.

RPG's from captured enemy cache

A Combined Intelligence Center, Vietnam (CICV) Study (ST 68-09, Logistics Fact Book), dated 14 April 1968, stated that the enemy used an intricate system of caches and depots from which supplies were distributed to their units. In the past, the enemy had used large central caches at locations which provided quick and easy access to units in the field. As allied operations uncovered and destroyed these large depots and caches, the enemy found it necessary to disperse them. The VC began to store rice in homes of private citizens, but there were still instances when they maintained large central depots. Most caches served as temporary consolidation points for out-of-country supplies coming into SVN for distribution to units. It also appeared that highly accurate records were maintained of the supplies in the caches but there was normally little reference to cache locations.

Caches varied in size as to their content, and the unit or operation they supported. One example of a VC directive on construction of storehouses (caches) and the maintenance of supplies and facilities, as published by Doan 84 (Group 84), Rear Service Unit, SVN Liberation Army Headquarters, is at Appendix 1(below). (The document was found in a hut by K/3/11th Armored Cavalry Regiment and translated by the Combined Document Exploitation Center, J2, MACV.) Caches were usually well concealed or camouflaged and search operations had to be thorough and methodical.

Pottery Weapons Cache

Emphasis was placed on evacuation of rice and other food caches for use by the GVN since evacuation of captured food caches served two important purposes. First, it denied the VC a much needed staple and second, it increased the food available to the local populace. However, evacuation was not always feasible due to the remoteness of caches, lack of helicopter or ground transport, and operational considerations which precluded units remaining in the area for an extended period of time. As stated by one commander, "Under some situations, it would be less expensive and more feasible to ship rice from Louisiana than to extract the same amount from the jungle caches." Destruction or denial measures then became necessary to prevent enemy retrieval of this critical resource. The requirement existed for a lightweight and effective system for contaminating or destroying large quantities of rice in a short period of time. The use of chemical contaminants was impractical for political/psychological reasons.

LOCATION AND DETECTION OF SUPPLY CACHES

On two occasions during OPERATION MANHATTAN, 1st Infantry Division interrogation of VC PWs led to the capture of two large VC weapons and munitions caches. One of these was the largest discovery of its kind at that time in Vietnamese war. Two VC officer PWs provided information concerning caches in the division AO. The most significant was located inside a concrete lined warehouse, guarded by a double ring of claymore mines. The caches contained;

The 199th Light Infantry Brigade, upon completion of OPERATIONS MANCHESTER, UNIONTOWN/STRIKE and UNIONTOWN I, reported that the VC had ingeniously used "anthills" to provide caches for small arms, munitions, grenades and claymore mines. On numerous occasions, natural anthills were found to be "hollowed out" in a manner not visible from the exterior. Each "hill" housed a cache from which individual defenders could replenish their ammunition stores as they either defended or withdrew. The 1st Infantry Division rendered a similar report upon completion of OPERATION CEDAR FALLS. Their observations were that weapons and munitions caches were generally located in bunkers resembling the anthills that were frequently found in the jungle. The bunkers had two entrances, were not booby trapped., and were located within 75 meters of a trail large enough to allow passage of an ox cart.

Upon completion of OPERATION MAKALAPA, the 1st Brigade, 25th Infantry Division reported that in the PINEAPPLE region (Northern Long An Province) all weapons and ammunition caches were located near canal banks and close to bunker complexes. The storage containers were usually 55 gallon drums or other metal containers buried at ground level with straw or other types of mats for lids. The Brigade also reported that areas which produced large caches of arms, medicine and other important supplies were heavily booby trapped. The booby traps were usually in a circular pattern around the cache and were sometimes marked with crude signs.

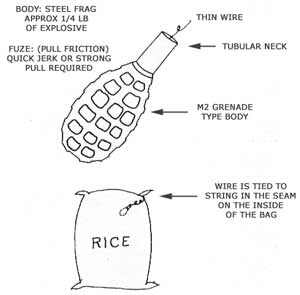

Rice Bag Booby Trap

The 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment reported that during OPERATION CEDAR FALLS any time a flock of small birds had been frightened away by approaching friendly troops, a large rice cache was discovered in the vicinity. Accordingly, any time a flock of birds was noticed, a search for a rice cache followed. It was also noted that intense booby trapping of a particular area was a good indication that valuable stores were hidden nearby.

The 173rd Airborne Brigade (Sep) reported, upon completion of OPERATION SIOUX CITY and THE BATTLE FOR DAK TO, that the use of scout dogs at company level aided in discovering enemy caches. However, it was noted that dogs became fatigued and were limited to approximately ten hours of work each day.

EXTRACTION and DESTRUCTION OF CACHES

The 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne), 1st Special Forces, reported that during a three month period when the bulk of the rice harvest had taken place within a province, units conducting combat operations had discovered large numbers of rice caches. Because of distances involved, and the location of these caches, it was difficult to extract or destroy this rice.

During OPERATION ATTLEBORO, the 1st Brigade, 1st Infantry Division found that rice located in crudely constructed bins could be effectively scattered by placing 43 pound cratering charges inside the bin and tamping them with loose or bagged rice. To preclude the use of scattered rice by the VC, CS in 8 pound bags was wrapped with one loop of detonating cord, spread over the scattered rice, and detonated. This unit further reported that a fast effective method for destroying bagged rice was to stack the bagged rice in a circular configuration, placing a 43 pound cratering charge in the center and tamping with bagged rice. Thirty to forty 200 kg. bags of rice were destroyed by one charge when using this method. All rice was so effectively scattered that contamination with CS was unnecessary.

Large enemy cache uncovered by 3/4

Cavalry

The 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division reported that VC rice caches, particularly the larger ones of twenty to one hundred tons or more, were often located in inaccessible areas and were extremely difficult to extract. One possible solution was to arrange with the District Chief or Province Chief before an operation began to have two hundred to three hundred porters under the protection of military forces, available and ready. Evacuation by helicopters had sometimes been accomplished, but the suitability of employing this method to remove large quantities of rice was questionable.

Upon completion of OPERATION WHEELER, the 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division reported that of the total rice tonnage (198.7 tons) captured by tactical elements of the brigade, 49.6 tons had been located in areas that were inaccessible to helicopters or, due to the tactical situation, could not be extracted. This rice was destroyed by engineer and chemical personnel by seeding the caches with CS and then scattering it throughout the area using cratering charges. A total of eight hundred and ninety three pounds of bulk CS powder was utilized in these operations.

During OPERATION MALHEUR, an eighty ton rock salt cache was discovered by A Co, 2nd Bn (Airborne), 502nd Infantry. It was not tactically feasible to extract the salt and therefore, it was decided to destroy the salt in place. Twenty, eight pound bags of CS were dispersed throughout the cache and blown simultaneously with a cratering charge, spreading the salt and CS throughout the area. The next day an additional four hundred and eighty pounds of CS was dropped on the cache from the air. A low level flight was made over the area seven days later and the CS concentration was still heavy; there were no signs of activity in the area or that any of the salt had been removed.

During OPERATION CEDAR FAILS, the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment (ACR) captured a considerable quantity of rice from widely dispersed caches in the IRON TRIANGLE. Since the 11th ACR could not extract or evacuate the rice, due to its combat mission, all possible means of evacuation were considered. Consideration was given to the use of surface transportation such as trucking companies. However, at the time there was insufficient transportation available to move the rice. Efforts were made to have the rice transported by the trucks organic to an ARVN Division. Although the request was not denied outright, the Division set a pickup date so far in the future as to be unacceptable. The 11th ACR then appealed to Province. After considerable pressure had been applied through advisory channels, the rice was partially extracted from the 11th ACR centralized collection point.

Enemy grenades being inventoried

During OPERATION MASTIFF, the 1st Infantry Division reported that an effective means of destroying rice by burning had been found. Gasoline, diesel oil and unused artillery powder increments were mixed with the rice to insure a hot fire. In this same operation, the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Infantry discovered a 50 ton rice cache which had been booby trapped. This rice was destroyed by pushing it into the Saigon River with a tank dozer. One other 75 ton rice cache was also destroyed by throwing it into the same river. During this same operation, a medical technical intelligence team was attached to the 3rd Brigade to examine and obtain samples of VC medical supplies taken from one of the base camps destroyed in the area. The team later reported that the antibiotics were of a type and brand that could be purchased on the open market in the Republic of Vietnam. The vitamin K (Ampoule K) found at the base camp was manufactured by laboratories TEVETE in Saigon. Large quantities of this item had been reported secretly captured by the VC in several places. The majority of the other drugs found were of the type normally found in VC captured medical supplies. The lot numbers and other information obtained from these medical supplies were of valuable assistance in determining and eliminating sources of supply to the VC.

SUMMARY OF SALIENT LESSONS LEARNED WITH RESPECT TO VC SUPPLY CACHES

Appendix 1 - Translation of VC document

Liberation Army

Doan 84

No. 44/cv "DETERMINED TO FIGHT AND DEFEAT US AGGRESSORS"

TO: Subordinates: K., K2., K3-, K7., C200. (Doan = Group; K = District; C = Company).

According to the agreement signed between Doan 84 and the local forward supply council; Doan 84 was to secure and store all supplies required for 1966 before August 1966. This agreement was sent to the various K (District). Now, we wish to remind you of building storehouses:

1. Based on the criteria of your branch, you should draft a specific plan for construction of various storage and issue sites.

2. You should use the requirements to calculate and estimate the materials and instruments needed for building the storages. The Group will study the estimate and approve the amount of money to be expended. At the same time, you must try by all means to purchase the necessary materials in advance in order to satisfy the immediate needs of holding the supplies.

3. During the rainy season, the provisions must be kept in high and dry places in order to prevent damage by termites and rain. Store keepers must kill termites, sweep the store, and repair leaks in the roof. The maintenance task must be looked after.

h. Following the construction of the storages, their defense must be rapidly set up to include: making fences, camouflaging, digging spike pits and laying minefields. Although temporary, the storages should be well camouflaged.

According to the criteria, each K (District) must have many caches which can accommodate assorted goods. The method of Construction should be carefully and scientifically studied. The caches must be appropriate to the goods. For example:

· Salt caches must be built underground. The floor should be lined with nylon sheets or straw. Only a small amount of salt should be stocked in the above ground storages.

· Salt fish should be kept in wooden airtight barrels set on stilts. They should be shaded with a roof.

· Rice depots: Cache frames must be set on stilts

· Clothing equipment storage: High, floored and with safe roof. This storage must be covered with curtains to shield light. Next to these curtains should be a layer of nylon or thatch used to prevent rain damage. Equipment must be set on the stilts. The blind must be tight so that mice cannot creep into the storage.

· Gasoline must be kept in cellars.

· Drug storages must be built as carefully as rice depots. Drugs should be set on a high and dry place.

Due to the great number of storages, the maintenance of storages must be concentrated. Ks (Districts):

· Know the number or storages, and the goods held in each store.

· Make a clear register in order to control issues and receipts.

· Unit leaders must control their storages and provide guidance for the cells.

Requisition and purchasing, transportation, and storage are three important tasks. Especially, in the storage task, the maintenance of goods is most important.

In the past, transportation was carried out well, but maintenance was still deficient.

You should try to step up this task because in the near future, provisions will be continuously sent to your unit in large quantity.

12 May 1966

Commander of Doan 84

NGUYEN VAN HUE

Method of preventing damage by termites:

In the maintenance task, some places applied an anti-termite method by using an aluminum plate. This method obtained favorable results. Now, we disseminate it to you for study and use:

Thus, when climbing up to the plate, the termites can not reach the girder, and must climb down.

INTRODUCTION

What

the Viet Cong (VC) and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) lacked in the way of

firepower they made up for in ingenuity. Concealed devices used to inflict

casualties, booby traps were an integral component of the war waged by Viet Cong

and People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) forces in Vietnam. These devices were used

to delay and disrupt the mobility of U.S. forces, in fact, the threat was often

enough to slow any advance to a snail's pace, divert resources toward guard duty

and clearance operations, inflict casualties, and damage equipment. They were a

key component in prearranged killing zones. Booby-traps could be covered by

snipers to further annoy the enemy or they might be the signal to spring an

ambush.

What

the Viet Cong (VC) and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) lacked in the way of

firepower they made up for in ingenuity. Concealed devices used to inflict

casualties, booby traps were an integral component of the war waged by Viet Cong

and People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) forces in Vietnam. These devices were used

to delay and disrupt the mobility of U.S. forces, in fact, the threat was often

enough to slow any advance to a snail's pace, divert resources toward guard duty

and clearance operations, inflict casualties, and damage equipment. They were a

key component in prearranged killing zones. Booby-traps could be covered by

snipers to further annoy the enemy or they might be the signal to spring an

ambush.

The use of booby traps also had a long-lasting psychological impact on Marines and soldiers and helped to further alienate them from civilian populations that could not be distinguished from combatants. The fear of booby-traps and mines was so great that units in the field (the boondocks) and the jungle (the zoo) were under stress the whole time. This created severe mental fatigue on both the commanders at platoon level and the individual soldiers.

Many of the materials for the mines and booby traps were of U.S. origin. These included dud bombs, discarded and abandoned ammunition and munitions, and indigenous resources such as bamboo, mud, coconuts, and venomous snakes.

The imaginative use of booby-traps by the NVA and VC caused many casualties amongst their opponents. Between January 1965 and June 1970, 11% of the fatalities and 17% of the wounds among U.S. Army troops were caused by booby traps and mines. To give one historical example, Charlie Company of the First Battalion, 20th Infantry sustained over 40% casualties in 32 days. They scarcely saw the enemy and took the casualties mainly from booby-traps and snipers. The effect on morale was such that these losses in men and the fact that they included virtually all of the experienced NCO's was said to have been more than partly responsible for the My Lai massacre that occurred.

Booby traps can be divided into explosive and non-explosive antipersonnel devices and anti-vehicle (i.e., tank, vehicle, helicopter, and riverine craft) devices. Antipersonnel booby traps were concentrated in helicopter landing zones, narrow passages, paddy dikes, tree and fence lines, trail junctions, and other commonly traveled routes. Anti-vehicle booby traps were deployed primarily on road networks, bridges, potential laager positions, and riverine choke points.

NON-EXPLOSIVE BOOBY-TRAPS

Non-explosive antipersonnel devices included punji stakes, bear traps, crossbow traps, spiked mud balls, double-spike caltrops, and scorpion-filled boxes.

By far the most common types of booby trap was the single punji stake. Punji stakes were sharpened lengths of bamboo or metal with needle-like tips that had been fire-hardened. Often they were coated with excrement to cause infection. Dug into shallow camouflaged holes and rice paddies and mounted on bent saplings, this was a common booby trap. Another similar device was a spiked mud ball suspended by vines in the jungle canopy with a trip-wire release. It functioned as a pendulum, impaling its intended victim.

The

simplest pit type was a hole about 20 to 30cm deep. The floor of this trap was

then set with punji stakes which could easily pierce the canvas and leather

jungle boot. For added misery the spikes could be smeared with poison or human

excrement to induce blood poisoning or worse. There were many variations which

allowed the spikes to attack the sides of the leg. This was particularly favored

after the introduction of the reinforced soled jungle boot.

The

simplest pit type was a hole about 20 to 30cm deep. The floor of this trap was

then set with punji stakes which could easily pierce the canvas and leather

jungle boot. For added misery the spikes could be smeared with poison or human

excrement to induce blood poisoning or worse. There were many variations which

allowed the spikes to attack the sides of the leg. This was particularly favored

after the introduction of the reinforced soled jungle boot.

Punji traps were laid wherever the enemy soldiers were likely to land with force. The purpose of the pit was to increase the downward force of a walking man. Such places included the places that soldiers would throw themselves to escape gunfire - ditches, behind logs, in long grass etc; or where they would land with some force - stream banks, likely helicopter landing zones etc.

Side

closing traps were also to be found. These ranged from the same size as the

punji pit up to man-sized traps. These were more sophisticated versions of the

punji pit and were likewise smeared with excrement or poison.

Side

closing traps were also to be found. These ranged from the same size as the

punji pit up to man-sized traps. These were more sophisticated versions of the

punji pit and were likewise smeared with excrement or poison.

The second group of non-explosive traps used some form of mechanism to set them off - usually a trip wire. The wire could be stretched across a track as a delaying tactic or linked to a hidden man to be released on command as part of an ambush or to hit a selected target.

The swinging man trap was positioned on jungle trails and heavily

camouflaged. It comprised a weighted beam pivoted so that when the pressure

plate was pushed down the other, spiked end swung upwards with enough force to

impale the victim. The target area was the chest in order to inflict a messy

fatal wound.

The bamboo whip was encountered on trails and was set off by a tripwire. It comprised a length of bamboo under tension and set with spikes (poisoned in the normal fashion) at chest height. The unfortunate victim would receive severe, it not fatal, wounds to the chest as it whipped across the trail

The spiked ball was another trap designed for jungle use. It was sprung by a trip wire which released the heavy clay ball set with sharp spikes. The force of gravity and the height of release combined to inflict horrific, usually fatal, wounds in the head and shoulders region.

The

bow trap was a favorite in the heavily forested mountainous areas - though it

was not limited to these. It too was tripped by a wire which released a

tensioned bow set in a shallow pit. The target area was the leg. The arrow was

normally tipped with poison or human excrement.

The

bow trap was a favorite in the heavily forested mountainous areas - though it

was not limited to these. It too was tripped by a wire which released a

tensioned bow set in a shallow pit. The target area was the leg. The arrow was

normally tipped with poison or human excrement.

.

EXPLOSIVE BOOBY-TRAPS

Variations of explosive antipersonnel devices encompassed the powder-filled coconut, mud ball mine, grenade-in-tin-can mine, bounding fragmentation mine, cartridge trap, and bicycle booby trap. The mud ball mine was a clay-encrusted grenade with the safety pin removed. Stepping on the mud ball released the safety lever, resulting in the detonation of the mine. The cartridge trap was a rifle round buried straight up and resting on a nail or firing pin. Downward pressure applied to the cartridge fired it into the foot of the intended victim.

These were normally set to give warning of an approaching force or as part of an ambush. They were also employed to slow down a follow-up force after an ambush or to cover a withdrawal. The generally poor quality of the grenades used by the VC and NVA combined with their (relatively) long fuse of 5-6 seconds made them much less effective than they might otherwise have been. If circumstances permitted captured US fragmentation grenades gave a much better performance.

The

simplest trap was a trip wire connected to one or two grenades. The grenades

were placed in tubes of bamboo or tins to keep the safety lever from releasing

when the pin was pulled. The victim tripped the wire, set at whatever height,

pulling the grenades from their containers.

The

simplest trap was a trip wire connected to one or two grenades. The grenades

were placed in tubes of bamboo or tins to keep the safety lever from releasing

when the pin was pulled. The victim tripped the wire, set at whatever height,

pulling the grenades from their containers.

Command-detonated grenade '~daisy chains" were set along trails where patrols were likely. These grenades were set close together to inflict casualties at a point where there would be a bunched target. Bunched targets could occur naturally at certain terrain features or be created by using other traps to create casualties and then hitting the evacuation teams. The number of grenades chained together would be dependant on the strength of the puller and the length of the wire.

Grenades

were also set in the ground below gates so that the slightest movement of the

gate would detonate it right below the victims' feet. In areas where the

vegetation closed above the trail grenades were often set to shower splinters of

wood and metal downwards, causing messy wounds which would require urgent

casualty evacuation.

Grenades

were also set in the ground below gates so that the slightest movement of the

gate would detonate it right below the victims' feet. In areas where the

vegetation closed above the trail grenades were often set to shower splinters of

wood and metal downwards, causing messy wounds which would require urgent

casualty evacuation.

Claymores were an especially lethal form of mine with both the US and Chinese versions hurling fragments in a 60 degree fan. The locations that were usually mined were roads, edges of roads, enemy escape routes from ambush sites, crossing places, village approaches, behind fallen logs, behind walls, gaps of any type and so on.

Dud shells and bombs were salvaged and turned into traps, mines or sources of explosives. The shell most commonly available for this was the 105mm artillery shell.

A

small variation of this used a 12.7 mm machine gun bullet set in a bamboo tube

with its primer resting on a nail or firing pin. The tip of the bullet just

protruded from the earth. A foot would press down sufficiently to set it off.

The bullet would explode shattering the victim's foot. If he was unfortunate

enough to be wearing the reinforced soled jungle boot then the steel or plastic

plate turned into shrapnel. The grunts called these 'toe poppers". They

were usually set in long grass.

A

small variation of this used a 12.7 mm machine gun bullet set in a bamboo tube

with its primer resting on a nail or firing pin. The tip of the bullet just

protruded from the earth. A foot would press down sufficiently to set it off.

The bullet would explode shattering the victim's foot. If he was unfortunate

enough to be wearing the reinforced soled jungle boot then the steel or plastic

plate turned into shrapnel. The grunts called these 'toe poppers". They

were usually set in long grass.

Traditional anti-personnel mines of all sorts from WW2 vintage onwards were used as they were intended and as part of booby-traps. One of the most common, and most hated, was the "Bouncing Betty". These mines were triggered by the release of pressure on the arming mechanism. Thus a soldier could stand on one, hear the arming mechanism operate and freeze. There he was standing erect knowing that if he moved his foot the mine would jump into the air and explode at chest height. Combat engineers came up with many extemporized methods of saving trapped soldiers.

The VC and NVA did not booby trap "souvenirs" to the same extent that the Japanese and Germans did in WW2. They did do it, but it was uncommon and possibly the more effective for that.

ANTI-VEHICLE TRAPS & MINES

Anti-vehicle devices included the B-40 antitank booby trap, concrete fragmentation mine, mortar shell mine, and oil-drum charge. The B-40 was a rocket-propelled antitank grenade, which in this instance was placed in a length of bamboo at the shoulder of a road and command-fired at a vehicle crossing its forward arc. The mortar mine was simply the warhead of a large-caliber mortar that had been separated from its body and retrofitted with an electric blasting cap. The oil-drum charge was based on a standard U.S. 5-gallon oil drum filled with explosives and triggered by a wristwatch firing device. This booby trap had immense sabotage applications for use against fuel dumps.

Soft vehicles could be destroyed by several of the anti-personnel mines or booby-traps described above. The VC and NVA used large numbers of mines to destroy enemy AFV's and were so proficient that the drivers and crews of the lighter sorts of AFV's rode on the outside of the vehicles. The crews of all vehicles would attempt to reduce the effectiveness of mine blast by putting layers of sandbags on the floor. This naturally affected the mobility of these vehicles. Some M-113's and M-551's were overloaded by doing this.

Captured artillery ammunition was prized for destroying tanks. The shell would be set in a culvert or similar location and command detonated under the track of the target. This was highly effective, particularly against the M-41's and M-551's. It was also very difficult to do correctly.

The habitual riding on the top of AFV's exposed the crews to sniper fire or to the anti-personnel traps set high enough to catch them. The threat must indeed have been real enough for the crews to accept the loss of their armour protection.

ANTI-HELICOPTER TRAPS

As the war progressed the prediction of likely helicopter landing zones became an art at which the VC and NVA became adept. The edges could be trapped or mined, the LZ's could also be mined or registered as mortar and heavy machine gun targets. However, a booby trap for helicopters consisted of wires connected to grenades atop posts at the edge of the LZ at a height to inflict blast and splinter damage on the debussing troops and splinter damage on the helicopters themselves, with the rotors being particularly vulnerable. Another particularly nasty anti-helicopter trap was the claymore mine sited on it's 'back' to fire up into the air as the helicopters were on final flare, sending hundreds of steel pellets through the soft belly of the helicopter. Still other mines were rigged into the tops of trees to be detonated by the rotor wash of nearby helicopters.

These devices were used on a scale never before encountered by U.S. military forces. As the war progressed and the casualty list stemming from booby traps mounted, U.S. forces employed numerous countermeasures. The most effective countermeasures were proactive in nature and focused on the destruction of underground VC/PAVN mine and booby trap factories and the elimination of raw materials used in the manufacture of such devices.

Tactical countermeasures included using electronic listening devices and ground surveillance radar; patrolling; deploying scout-sniper teams and Kit Carson Scouts; booby trapping trash left by a unit; and employing artillery ambush zones. Principal individual countermeasures were wearing body armor, sandbagging the floors of armored personnel carriers (APC's), and abstaining from the collection of "souvenirs".

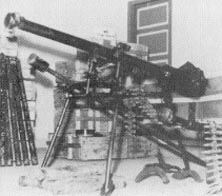

Characteristics of NVA & VC Smallarms

During the early war years, the VC relied on a mix of weapons from various sources; captured French and Japanese weapons, US made .30 caliber M-1 (semi-automatic) and M-2 (semi- and full automatic) carbines and the .45 caliber Thompson M1928A1 as well as other SMG's such as the 9mm MAT-49 and the 7.62mm PPSh-41. Many of these weapons came by way of capture as well as international arms sales. However, as supplies from the North began to filter down into RVN, new weapons from the Russians and Chinese began to make their appearance.

Synonymous with the NVA regulars and Vietcong Mainforce units, the basic infantry weapon was the Soviet 7.62mm AK-47 assault rifle, or the Chicom copy Type 56. Whilst the Chicom Type 56 was the predominant rifle, the weapon was referred to generically as the AK-47 irrespective of the country of origin. Capable of firing semi- or full automatic at the flip of a switch the AK-47 was issued in several different configurations.

Almost as equally widespread as the AK-47 was the Soviet 7.62mm SKS carbine or Simonov, a semi-automatic rifle which was especially common amongst the regional and local VC forces.

Left to Right: SKS carbine, RPD LMG,

AK-47

By the time of the Tet offensive in 1968, the NVA and Main Force VC were almost universally armed with modern Soviet or Chicom weapons although the regional and local VC forces still carried weaponry of mixed vintage. Main Force VC units around 1965 - 1966 were generally armed in the same manner as their NVA counterparts and there is much evidence which exists to suggest that Main Force VC consisted of substantial numbers of early war NVA regulars.