Society of the 9th

Infantry Division

-SONID-

9th Infantry Division

History

Webmaster's Note: Many of the Figures shown below are repeated as text to make sure all viewers, regardless of their browser, will be able to view the information.

Click to view

Courtesy of Robert Fisher. To view additional

information and photos go to his web site Back

In The Delta

(The above items are large and may take over a minute to completely load over a

56k modem)

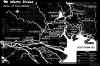

LEFT: Listing of units assigned to or working with the 9th Infantry Division -

January-July 1969

RIGHT: Map of the 9th Infantry Division Area of Operation - January-July 1969

A Brief History of the 9th Infantry

Division

(Copyright: Karl Lowe, 2003)

Courtesy of:

Index

(Scroll down and read

the entire document below or select from the Index below and use your BACK

BUTTON to return here)

World

War I (1918-1919)

1923-1940

World

War II & European Occupation (1940-1947)

1957-1962

Vietnam (1966-1970)

1972-1982

1982-1991

9th ID Campaign Credits

9th

ID Decorations (shown only to Brigade level)

Medals of Honor

9th

Infantry Division Duty Stations

9th ID Temporary Wartime

Attached Units

The 9th Division was organized on July 5, 1918 at Camp Sheridan (Montgomery), Alabama.[1] The 45th and 46th Infantry Regiments, formed a year earlier at Ft Benjamin Harrison, Indiana, were the first units to join the division, providing cadre for the 67th and 68th Infantry Regiments, respectively, to give the division it’s authorized “square” configuration. The division soon blossomed as a plethora of support units were added. At full strength (Figure 1), the division would total around 24,000 men. The 9th expected to go to France when it reached full strength, but the war ended before it could get into the fight. No longer needed, it was partially demobilized at Cp Sheridan on February 15, 1919 and Cp Sheridan was closed. The 18th Infantry Brigade’s Headquarters Company and the 45th and 46th Infantry Regiments moved to other posts.[2]

Figure

1

9th Division (1918-1919)

Special

Troops

Division Trains

9th Field Artillery Brigade

HQ Company

HQ & MP

Company

HQ Battery

Field Signal Battalion

Supply Train

25th

FA Regiment (75mm)

Engineer Regiment

Ammunition Train

26th

FA Regiment (75mm)

Heavy Machinegun Battalion

Engineer Train

27th FA Regiment (155mm)

Sanitary Train

9th Trench Mortar Battery

2 Ambulance Companies

2 Field

Hospitals

17th

Infantry Brigade

18th Infantry Brigade

HQ Company

HQ

Company

45th Infantry Regiment

46th

Infantry Regiment

67th Infantry Regiment

68th Infantry

Regiment

25th Machinegun Battalion

26th

Machinegun Battalion

The 18th Infantry Brigade remained active throughout the interwar years, carrying on the 9th Division’s lineage. In 1921, its headquarters moved to Ft Warren (Boston), Massachusetts. Its components were stationed at small posts all over New England.[3] Assigned to I Corps, the brigade’s primary mission was training units of the Reserve Officer Training Corps, the National Guard, and the Organized Reserve Corps in New England. In the 1930s, it also gained responsibility for running Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps camps in New England. Because it was recruited where Ivy League colleges were the center of attention, the 18th Brigade began referring to itself as “The Varsity”. The name was allegedly adopted after the brigade’s rough and tumble football team beat Harvard in a 1927 exhibition game in Boston. The name stuck well into the 1940s.

[1]

The site is now Gunter Air Force Base, home of the Air Force NCO Academy.

[2]

The 45th and 46th Infantry were reassigned elsewhere in

1918. The 45th was

reduced to just its officer cadre and deployed to the Philippines in 1921 to

become a Philippine Scout unit. It

distinguished itself at Bataan in 1942. The

46th moved to Cp Travis, Texas and was inactivated there in 1921.

Neither regiment served with the 9th Division again.

[3]

The 5th Infantry Regiment was stationed at Ft Williams, Ft McKinley,

and Ft Preble near Portland, Maine; the 13th Infantry Regiment was at

Ft Strong and Ft Andrews on islands near Boston and at Ft Adams, in Newport,

Rhode Island. The 9th Tank Company was subsequently formed at Ft

Devens, near Ayer, Massachusetts and the 2d Battalion 25th FA was

formed at Madison, Barracks, in upstate New York to give the brigade a fire

support component.

The 9th was restored to the rolls in

1923 (Figure 2), but it was a division only on paper, with most units assigned

at zero strength. The 18th

Infantry Brigade remained its only active component. When shoulder patches were made official throughout the Army

that year, the 9th Division adopted the “octofoil”, which its

soldiers have worn ever since.[4]

The octofoil is a 15th Century device denoting the ninth

brother, a disc centered in a ring of eight foils (points), denoting the

center’s protective older brothers. The

red foils on top symbolize the division’s artillery, the blue foils symbolize

the division’s infantry foundation, the white disc in the center completes the

national colors, and the olive drab background was color of the Army’s

uniform.

The 9th was restored to the rolls in

1923 (Figure 2), but it was a division only on paper, with most units assigned

at zero strength. The 18th

Infantry Brigade remained its only active component. When shoulder patches were made official throughout the Army

that year, the 9th Division adopted the “octofoil”, which its

soldiers have worn ever since.[4]

The octofoil is a 15th Century device denoting the ninth

brother, a disc centered in a ring of eight foils (points), denoting the

center’s protective older brothers. The

red foils on top symbolize the division’s artillery, the blue foils symbolize

the division’s infantry foundation, the white disc in the center completes the

national colors, and the olive drab background was color of the Army’s

uniform.

In October

1939, the 18th Infantry Brigade deployed to Panama to help protect

the Canal. There were fears in

Washington that Germany or Japan might try to grab the strategic waterway or

seek to destroy it with a commando raid. In

its new assignment, the brigade had to tear off its octofoil shoulder patches

and sew on the Panama Defense Command’s insignia.

For the first time since 1918 there was no longer an active component of

the 9th Division.

[4]

The division’s earlier unofficial shoulder patch, adopted at Cp Sheridan, was

a shield with its top half red, bottom half blue, and a gold “9” in the

center.

On August 1, 1940, the 9th Division was

reactivated at Ft Bragg, North Carolina.[5]

In contrast to its cumbersome World War I “square” configuration, the

new 9th was organized as a streamlined “triangular” division,

organized as shown in Figure 3. Only

the 26th Field Artillery could claim a historical link to the

original 9th Division formed in 1918.

On August 1, 1940, the 9th Division was

reactivated at Ft Bragg, North Carolina.[5]

In contrast to its cumbersome World War I “square” configuration, the

new 9th was organized as a streamlined “triangular” division,

organized as shown in Figure 3. Only

the 26th Field Artillery could claim a historical link to the

original 9th Division formed in 1918.

The division underwent eight months of individual and unit training and a month-long division-scale exercise. The “Varsity” completed its graduation exercise at Ft Bragg in April 1941 and became combat ready. In October and November of that year, the division participated in the Carolina Maneuvers, followed by amphibious training on North Carolina’s outer banks, a chain of barrier islands along the Atlantic coast.

[5]

The 36th and 37th Infantry Regiments were concurrently

relieved from assignment without having seen a day of active service with the

division. The 18th

Brigade in Panama was also relieved from assignment.

[6]

France held a deep grudge against Britain, America’s partner in the North

Africa landings, because Britain had bombed the French fleet at Mers el-Kbir,

Algeria in 1940 to keep it from falling into German hands after France

surrendered.

The 9th did not initially operate as a division in North Africa. Its 39th Infantry Regimental Combat Team (RCT)[7] landed in Algeria under the Eastern Task Force, while the 47th and 60th RCTs landed in French Morocco under the Western Task Force. The 47th RCT took the Moroccan port of Safi, allowing elements of the 2d Armored Division to land unopposed and attack toward Casablanca. The 60th RCT landed near the French garrison city of Port Lyautey, Morocco where it encountered tougher resistance. Aided by naval gunfire, the 60th RCT took the nearby airfield on the first day, but it took two more days of hard fighting to take the city. French resistance ceased on November 11, a date laden with irony since it was the anniversary of World War I’s end. Troops that had just fought bitterly against Americans and the British, suddenly became allies against the Germans. Trust would take longer to develop.

When the

Germans were driven from Libya into Tunisia by the British Eighth Army in

February 1943, the 9th Division moved over a thousand miles from the

border of Spanish Morocco to join the fighting.

Its 60th RCT was attached to the 1st Armored

Division on March 12 and took the important road junction of Sened Station nine

days later. The 9th

Infantry Division fought as an entity for the first time on March 28, 1943.

Attacking from positions abandoned earlier by the 1st Infantry

Division, it tried to open a path for the 1st Armored Division, but

was repulsed with heavy losses. A similar attempt to isolate and capture Hill 772, which

dominated the area, also met with failure.

Finally, in a corps-level effort alongside the 1st Infantry

Division, the 9th broke through German lines and established contact

with advanced patrols of the British Eighth Army.

On April 11,

the 9th relieved the British 46th Infantry Division in

northern Tunisia. Reinforced by the

French Corps d’Afrique, the 9th

attacked along the Sedjenane Valley toward the port of Bizerte, through which

German and Italian troops were trying to escape across the Mediterranean to

Sicily. The attack began from a

string of hills west of Sedjenane on April 23 and ended on May 8 when the 47th

RCT and the Corps d’ Afrique entered

Bizerte. The war in North

Africa ended five days later when remnants of the Italian First Army surrendered

to British forces near Tunis.

For the 9th

Infantry Division, the war in the Mediterranean was still not over.

The division landed at Licata, Sicily on September 15, 1943, five days

after the initial allied landings to enter combat in northern Sicily on July 23.

Pushing itself to near exhaustion across a long string of hills just

north of Mount Etna, the 9th Division outflanked the German 15th

Panzer Grenadier Division, rendering its foe’s carefully-prepared defenses

useless. Its unexpected speed

forced the Germans to evacuate Troina where they had held up the 1st

Infantry Division for days. The 9th

then raced the US 1st and 3d Infantry Divisions and the British 78th

Division toward the port of Messina where the Germans and Italians were

struggling to evacuate their remaining forces across the Straits of Calabria to

Italy. After running out of

passable roads in its sector, the 9th’s attack ended, but it had

done its job admirably. By October

17, the battle for Sicily was over.

[7]

A regimental combat team was formed around an infantry regiment (3 infantry

battalions), reinforced by a field artillery battalion, a combat engineer

company, and sometimes a tank battalion or tank destroyer battalion.

After its

well-executed offensive in northern Tunisia and its lightning dash across

northern Sicily, the 9th was becoming known as one of the Army’s

most reliable divisions. Because of

its performance, it was among the divisions selected for redeployment to England

in preparation for the coming invasion of Europe.

It left Sicily on November 8, 1943, exactly a year after landing in North

Africa, and reached England on November 25.

In England, the 9th was assigned to the US First Army and began preparing for the coming invasion of France. After six months in England, it landed on France’s Normandy coast on June 10, 1944. Following the path of the 4th Infantry Division, the 9th crossed Utah Beach and took the German gun positions dominating the beach head. The 39th RCT, spearheading the attack, earned its nickname “anything, anywhere, any time--bar none” in hard fighting against German units that had held up the 82d Airborne and 4th Infantry Divisions for nearly a week.

After a brief rest, the 9th crossed the Seine River on August 27, driving north toward the Belgian border. Belgium’s liberation began when a patrol of the 9th Reconnaissance Troop crossed the border near Charleroi at 1107 on September 2, 1944. For the next 12 days, the division pushed across southern Belgium to the frontiers of Germany, crossing the border through an array of concrete barriers and bunkers with interlocking fire known as the Siegfried line. It took five more days of hard fighting, but the 9th got through, exposing the southern approaches to the city of Aachen, the first German city to fall to the allies. The 1st Infantry Division would have the honor of taking Aachen, but it was the 9th that opened the door.

On December 22, 1944, a platoon of E Company 39th Infantry, led by Technical Sergeant Peter J. Dellesondro, held a road junction under attack by a battalion of German paratroopers. Their attack followed right on the heels of a nerve-shattering mortar and artillery concentration. Dellesondro’s men, expecting their position to be overrun, began to abandon their positions under heavy fire but he managed to keep the platoon together by moving constantly up and down the line, shouting and shoving or dragging his terrified men back to their foxholes. He worked his way to an exposed observation point to direct mortar fire against the Germans nearing his line. His accurately placed fire stopped the Germans initially, but when the mortar fire lifted, they resumed their attack, concentrating their fire against Dellesondro’s prominent position. When his rifle ran out of ammunition, he crawled 30 yards across open ground to reach a machinegun, which he fired until it jammed. After clearing a jammed cartridge from the gun’s chamber, he fired another short burst to keep four Germans from killing one of his medics who was trying to give first aid to two wounded soldiers in a foxhole. Again the gun jammed and became useless. When his platoon was surrounded, he threw hand grenades until he ran out and then called in mortar fire on his own position, buying time for his company to block a further German advance. He was captured but survived to be presented the Medal of Honor after the war.

[8]

Sheridan Kaserne, in Augsburg, Germany was named after him during

Germany’s subsequent occupation. Nelson

Barracks at Neu Ulm was named after another of the 9th Division’s

Medal of Honor winners, William L. Nelson of the 60th Infantry

Regiment.

Because all bridges across the Rhine had been blown but one, the First Army pressed its attack to capture the remaining bridge before the job got any harder. Arriving just behind the 9th Armored Division, which captured the Ludendorff Bridge on March 7, the 9th Infantry Division surged across to widen the bridgehead. For six days, it held the contested east bank of the Rhine, taking command of a small corps as an array of units from other divisions and corps troops crossed the river under the direction of the division’s 9th MP Company. MPs steadfastly stood at their posts on the bridge without protection from steady German shellfire and air attacks. When one MP went down, another took his place. MPs forced drivers who tried to abandon their vehicles on the bridge during an air attack, to get back in their vehicles and continue driving. In more than one case they had to do so at gunpoint, but they kept the convoys rolling.

The “Old Reliables” remained inactive for only

six months. It was reactivated at

Ft Dix, New Jersey on July 15, 1947. Ft

Dix was the division’s last stateside post before being shipped off to North

Africa in 1942 and its first post when it returned. Organized at cadre strength (Figure 4), the division’s

mission was to conduct basic and advanced individual training for soldiers

recruited in the northeastern states. On

May 25, 1954, the 69th Infantry Division assumed the training mission

at Ft Dix and the 9th Division’s colors were sent to Germany,

replacing the Pennsylvania National Guard’s 28th Infantry Division,

which had relieved the 9th in the Huertgen Forest nearly a decade

earlier.

The “Old Reliables” remained inactive for only

six months. It was reactivated at

Ft Dix, New Jersey on July 15, 1947. Ft

Dix was the division’s last stateside post before being shipped off to North

Africa in 1942 and its first post when it returned. Organized at cadre strength (Figure 4), the division’s

mission was to conduct basic and advanced individual training for soldiers

recruited in the northeastern states. On

May 25, 1954, the 69th Infantry Division assumed the training mission

at Ft Dix and the 9th Division’s colors were sent to Germany,

replacing the Pennsylvania National Guard’s 28th Infantry Division,

which had relieved the 9th in the Huertgen Forest nearly a decade

earlier.

[9]

They were Herschell F. Briles (899th

Tank Destroyer Battalion), Peter J.

Dellesondro (39th Infantry), William

L. Nelson (60th Infantry), Carl

V. Sheridan (47th Infantry), and Matt Urban (60th Infantry). Briles’, Nelson’s, and Sheridan’s medals were presented

posthumously.

In August 1956, the 9th rotated to Ft Carson, Colorado under Operation Gyroscope. The following year, it was reorganized under the “Pentomic” concept (Figure 5). The reconfigured 9th Infantry Division remained at Ft Carson until its inactivation on January 31, 1962.

For the next four years, the division’s colors remained furled, but when war came again, “the Old Reliables” returned to active service. The division was reactivated at Ft Riley, Kansas on February 1, 1966. On December 19, 1966, Major General George S. Eckhardt led the division ashore across the beach at Vung Tau, Vietnam. He was met by General William C. Westmoreland, who had commanded an artillery battalion with the division in World War II and later became the division’s Chief of Staff and Commander of the 60th Infantry Regiment during the occupation of Germany.

The division

would operate initially from Bearcat Base (Camp Martin Cox), east of Saigon.

Its area of operations had been owned by the Viet Cong (VC) and their

Viet Minh[10]

predecessors since the early in the war of liberation against the French.

For the next four years, the octofoil shoulder patch would become a

familiar sight around Saigon and along the labyrinth of waterways lacing the

upper Mekong River Delta. The

division’s organization (Figure 6) reflected its unique mission.

The 1st and 3d Brigades each had two standard infantry

battalions and a mechanized infantry battalion, while the 2d Brigade, with three

standard infantry battalions, was organized for riverine operations, living and

operating from ships and river patrol boats operated by the US Navy’s Task

Force 117.

[10]

The terms Viet Minh and Viet

Cong derive from “Viet Nam Duc Lap

Dong Minh Hoi” (Independence Party), Vietnam’s Communist (Cong

San) Party.

The division’s first combat operation of the war was Operation Colby, initiated on January 20, 1967 to drive the VC out of an area called the “Phuoc Chi Secret Zone”. While a small operation, Colby heralded the division’s reach into an area of operations that was to expand to 7000 square miles. Soon afterward, 3-5th Cav, the division’s armored cavalry squadron, participated in Operation Junction City, operating northeast of Saigon alongside the 1st and 25th Infantry Divisions and the 196th Light Infantry Brigade.

In March,

elements of the 3d Brigade fanned out across Long An Province, establishing fire

support bases at Tan An (3d Bde HQ and HHB 2-4th FA), Tan Tru (2-60th

Inf), Binh Phuoc (5-60th Inf), and Rach Kien (3-39th Inf).

The brigade’s first big fight occurred when a company of the 3-39th

Infantry was attacked and overrun in its night defensive position at a road

junction 4 km north of Rach Kien. The

brigade responded like a coiled snake the next day, attacking the VC 2d Long An

Battalion in its base area along Doi Ma Creek, west of Rach Kien. The enemy paid with the lives of 209 of its men.

In May, the 2d

Brigade conducted a riverine operation in eastern Long An Province near Ap Bac.

Soon after crossing a deep stream, A Company 3-47th Infantry

ran into intense rifle and machinegun fire and rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs).

Soon every man in the lead squad was dead and several more were killed as

they tried to save their buddies. Most

members of A Company were wounded. Piling

on any unit he could grab, Colonel William B. Fulton, the brigade commander,

threw companies from three battalions into the fight.

By late afternoon, A and B Companies 3-60th, and C Company

5-60th Infantry had reinforced the 3-47th.

The ARVN 1st Battalion 46th Infantry (of the ARVN

25th Division) blocked the enemy’s escape route to the south.[11]

The VC 514th Battalion would soon pay dearly for what it had started.

By 1900, the

counterattack, led by “Bandido Charlie” (C/5-60th Infantry),

surged across the soggy paddies in armored personnel carriers while riflemen

from five other rifle companies closed in on the nearby tree line.

During the ensuing fight, Sergeant Leonard Keller and Specialist Raymond

R. Wright of A Company 3d Battalion 60th Infantry earned the Medal of

Honor for their fierce two-man assault that knocked out a string of bunkers and

a mortar position with rifles and hand grenades and then chased the VC out of an

area where several men had been wounded.

The fighting was hand-to-hand throughout the tree line.

GIs wanted revenge for what had happened to their comrades back at the

creek. One man beat an enemy

soldier to death with his steel helmet after his weapon jammed.

Another stabbed an enemy soldier to death under similar circumstances.

Nightfall brought the fighting to a close as surviving enemy troops

slipped away. In the end, 15

Americans and 181 VC had been killed.

On September

14, it was 3-60th Infantry’s turn to get in trouble.

Moving by river patrol boat, the battalion advanced up the narrow Ba Rai

Creek, a nipa[12]-lined

tributary of the Mekong. It was

followed by 3-47th Infantry, also on boats.

The boats were spaced about 50 feet apart but in places the shore was 15

feet or less from the boat’s sides. Suddenly

at 0730, two RPGs struck the lead boat. Four

more RPGs soon followed, turning it into a floating wreck and killing two of its

crew but its skipper stubbornly kept his boat in action.

Throughout the day, fighting raged all along the canal, with enemy fire

coming from both banks of the creek. Helicopter

gunships, fighters, artillery, and Navy “Black Pony” attack aircraft added

their fires to those of the well-armed patrol boats.

As the fight progressed, elements of four American infantry battalions

piled into the swampy terrain by boat and helicopter to box the enemy in.

Aboard the boats, 7 men had been killed and 123 wounded. As night fell, the enemy was more interested in slipping away

than continuing the fight and by morning the battlefield’s stillness was

broken only by the droning roar of river boats leaving the area.

[11]

This ARVN battalion operated routinely with the US 9th

Division, something the ARVN 25th Division Commander, BG Truong Chinh,

tolerated grudgingly. The author of

this short division history was the battalion’s senior advisor during the

battle.

[12] Nipa is a palm that grows profusely along the banks of

rivers, streams, and canals throughout Southeast Asia.

It grows to a maximum height of only 10 feet, but its thick trunk, dense

growth pattern, and deep roots make it a formidable defensive barrier, used

extensively by the Viet Cong to shelter temporary base areas and weapons caches.

On November 18,

a battalion-size attack on an artillery fire support base near the vital road

junction of Cai Lay sparked another bitter fight. At 0200, enemy mortars were striking at a rate of about 3 per

minute, keeping crews from servicing their weapons. Seeing an enemy platoon forming to attack across an adjacent

stream, PFC Sammy L. Davis, a cannoneer with C Battery, 2d Battalion 4th

FA, grabbed a machinegun and sprayed the enemy to give his fellow crewmen time

to recover and fire their howitzer. An enemy recoilless rifle round struck the

weapon, disabling the entire crew and setting the position on fire.

Although stunned by the blast, Davis ran to the weapon alone, slammed a

shell into the breech, and fired point blank at the enemy assault force.

The unstaked howitzer’s recoil sent Davis sprawling, but he got up and

fired 4 more shells into the oncoming enemy force.

A mortar round struck 20 yards away, wounding Davis, but it did not stop

him. Adrenalin had taken control.

Davis grabbed an air mattress because he could not swim and paddled

across the stream to rescue 3 wounded men stranded at an isolated observation

post. As the men escaped across the

stream, Davis stood and fired his rifle into the tall grass surrounding the OP.

Davis then returned to his gun position aboard the air mattress and joined

another howitzer crew firing on the fleeing enemy.

For his exceptional courage and determination under fire, Davis was

awarded the Medal of Honor.

On January 10,

1968, a daylong fight broke out in Dinh Thuong Province when an airmobile

assault by A Company 3-60th Infantry went sour.

Enemy rifles, machineguns, mortars and RPGs struck the company from three

sides as it landed. Within minutes, 30 men were down. Aidman PFC Clarence E. Sasser disregarded his own safety and

several painful wounds to dash back and forth through the fire to drag men to

the protective cover of a paddy dike. Even

after both legs were immobilized by painful wounds, Sasser continued to crawl

among the wounded to administer life-saving aid.

He continued his unrelenting effort for over five hours under continuing

enemy fire. He was awarded the Medal of Honor.

On January 30,

1968, the people of Vietnam were about to celebrate the lunar New Year, the

country’s most important holiday. Viet

Cong and North Vietnamese Army units had been moving into position around major

South Vietnamese cities for over a month, however, and their support elements

had stockpiled caches of ammunition near important places they were to attack.

The scale, focus, and intensity of the enemy’s attacks on Vietnam’s

cities caught senior officials by surprise.

In the Saigon area, “the Old Reliables” seemed to be everywhere at

once. On the offensive’s first

day, 2-47th Mechanized Infantry and 4-39th Infantry fought

on the city’s northern approaches to protect part of the Army’s sprawling

headquarters and support complex at Long Binh; 3-5th Cavalry fought

at nearby Bien Hoa Air Base; and 5-60th Mechanized Infantry fought on

the city’s west side at the Phu Tho race track.

In the fighting

at Long Binh, the VC had infiltrated and fortified the “widow’s village”,

a complex of shacks adjacent to US II Field Force Headquarters.

The area was inhabited mainly by widows and families of dead ARVN[13]

soldiers. When rockets and mortars began to rain down on II Field Force

Headquarters from the “village” and a nearby wooded draw, 2-47th

Mechanized Infantry was rushed in from the base’s southern perimeter.

Riding into a storm of RPG, mortar, and automatic weapons fire, the

battalion became engaged in a fight it could not win alone.

More infantry would be needed to clear the labyrinth of well-prepared

enemy fortifications. In response,

4-39th Infantry arrived by helicopter, landing in a “hot LZ”, a

term meaning the enemy controlled the landing zone and were firing on the

helicopters as they landed to disgorge troops.

Supported by attack helicopters from Bien Hoa and other nearby bases, the

two battalions launched a coordinated attack to clear the area.

By nightfall, over 200 enemy soldiers lay dead in the shattered ruins of

the “widow’s village” and another 32 were captured. Four Americans died in the action.

At Bien Hoa Air

Base, 3-5th Armored Cavalry rushed onto the eastern end of the

airfield and a nearby wooded area with all guns blazing.

The close-in fighting, like that at Long Binh, raged all day and into the

night. 40 enemy soldiers and 3

members of 3-5th Cavalry had been killed by the time enemy troops

were driven off the airfield. At

the French military cemetery[14]

near the Phu Tho race track, 5-60th Mechanized Infantry encountered

snipers in the trees and a line of hasty earthen bunkers from which the

interlocking fires of a VC battalion protected a rocket and mortar unit located

in the courtyards of nearby buildings. Heavy

fighting continued all day and all night, tapering off into sporadic outbursts

for the next four days as trapped enemy troops tried to fight their way out of

the city. 125 of them died trying.

On the city’s southern edge, elements of the 3d Brigade retook Cholon

District and fought their way up the city’s east side along the Saigon River.

In Kien Hoa

Province at edge of the Mekong Delta, an enemy battalion overran the provincial

capital of Ben Tre, driving government officials and advisors into a walled

compound in the city’s center. Their

desperate call for help brought 3-39th Infantry into the center of

town in a daring air assault while 2-60th Infantry fought

house-to-house from the city’s east side and 2-39th Infantry fought

its way in from the southwest. Two

battalions of the ARVN 7th Division closed in from the north, their

American advisors coordinating their fires and maneuver with adjacent US units.

160 enemy troops and 11 Americans died in fighting that lasted three days and

left Ben Tre utterly destroyed. It

was not a satisfying victory.

3-5th

Armored Cavalry was again in action on 2-3 February, 1968 when the Viet Cong

besieged a police station and provincial government compound at Xuan Loc,

northeast of Saigon. Enemy RPGs and

automatic weapons fire lashed out from both sides of the city’s main street as

3-5th Cavalry charged in on armored personnel carriers, but the

cavalrymen were able to rescue the trapped policemen and helped the ARVN 18th

Division secure the government complex. The

fighting did not end there, but continued for two more days in a nearby rubber

plantation.

At My Tho, the

capital of Dinh Thuong Province and one of the Delta’s largest cities,

infantrymen of the Mobile Riverine Force stormed ashore to help the ARVN 7th

Division retake the city. The Viet

Cong 261st, 263d, and 514th Main Force Battalions fought

hard to hold onto the city but were driven out by determined “Old Reliables”

of the 3-47th and 3-60th Infantry blasting their way

through walls and down alleyways to break up the enemy’s cohesion.

To care for civilian casualties, Lieutenant Colonel Travis Blackwell, the

9th Division Surgeon, flew into the city’s center with a surgical

team to help man the city hospital’s four operating suites.

Because the hospital was too crowded, Blackwell established an operating

area in a protected street where he performed 35 operations on the battle’s

first day alone. Under fire for

three days, Army doctors and nurses took care of the injured around the clock

with no time to rest.

By February 4,

the ARVN 21st Division had lost control of the important delta city

of Vinh Long where the VC 306th and 857th Battalions had

been on the offensive since the night of January 31. Troops of the 2d Brigade were rushed by boats and

helicopters from the fighting at My Tho to help retake Vinh Long. After driving the VC out of the city on February 5,

infantrymen of the 2d Brigade, backed by Navy “monitor” river boats and Army

attack helicopters, pursued the retreating enemy along the nipa-lined Ba Moi

canal. In its attempt to cover the

withdrawal of the 306th Main Force Battalion, the VC 857th

Local Force Battalion was nearly destroyed.

The following

day, B Company 3-60th Infantry was ambushed aboard river boats

patrolling a stream thought to be one of the VC escape routes from Vinh Long.

As riflemen struggled through the dense nipa growth to drive the

ambushers out, an 8-man squad of B Company was cut off under heavy fire.

When an enemy hand grenade landed in the squad’s midst, PFC Thomas J.

Kinsman threw himself on the grenade to save his comrades.

Although severely wounded in the head and chest, Kinsman miraculously

survived the blast. For his act of

selflessness, he was awarded the Medal of Honor.

On an operation

south of Saigon on March 17, 1968, B Company 4-39th Inf encountered

heavy fire from enemy bunkers dug into a nipa-lined stream.

One man was killed and 3 were wounded in the initial outburst of fire.

Specialist Edward A DeVore, Jr rushed forward to cover the evacuation of

the wounded with his machinegun. Recognizing

the wounded men’s situation was nearly hopeless unless someone could quell the

enemy fire, he assaulted the enemy position, firing his machinegun from the hip

as he rushed forward across open ground. Hit

in the shoulder and knocked off his feet just 35 meters from the enemy, DeVore

got back up and continued firing, drawing all enemy fire unto himself as his

comrades evacuated the three wounded men.

He was killed just moments later. For

his selfless act of extraordinary valor, he was awarded the Medal of Honor.

On May 7, 1968,

the VC made a second attempt to take Saigon, although a weaker attempt than the

Tet Offensive in February. Enemy

action was centered on the predominantly Chinese district of Cholon at the

city’s southeastern edge. After

taking the Y Bridge over the Kinh Doi Canal, a VC/NVA regiment established

itself in houses overlooking the bridge and adjacent areas along the canal.

2-47th Mechanized Infantry, reinforced by the newly-arrived B

Company 6-31st Infantry[15],

retook one side of the bridge and drove the enemy into a cement factory where an

ARVN Ranger Battalion scaled the surrounding walls and fought its way into the

center with support from US helicopter gunships. Meanwhile, south of the city, 3-39th Infantry and

ARVN 3d Battalion 46th Infantry turned back an attempt to reinforce

the VC unit trapped in Cholon. Along

the Kinh Doi Canal defining the city’s southern edge, the rest of the 6-31st

Infantry landed by helicopter under intense fire. Firing into houses lining the canal, the battalion turned

west along the perimeter road to secure two smaller bridges across which the

enemy might try to escape.

At 6:00 the

next morning, the 6-31st Infantry responded to an enemy attack on an

ARVN Regional Force outpost at the city’s edge while 3-39th

Infantry entered an adjacent part of the city where the enemy had prepared hasty

bunkers to block alleyways the night before.

The fighting raged until 7:30 that evening. Supported by artillery, attack helicopters, and 2-47th

Infantry’s APCs, companies from the 3 US battalions and ARVN troops drove the

enemy out block by block in some of the war’s most desperate fighting.

Knowing they could not escape, the VC fought like cornered rats.

Over 1000 of them died, as did 50 members of the 9th Division

and an unknown number of ARVN troops. Civilian

casualties in Cholon are also unknown, but must have numbered several thousand

dead and wounded.

On May 14,

1968, 3 VC were ambushed by a rifle squad of the 4-47th Infantry in

Kien Hoa Province. Two of the VC

were killed instantly, but a third threw a grenade at the squad to cover his

escape. PFC James W. Fous leaped on

the grenade to save his comrades. He

was awarded the Medal of Honor for sacrificing his own life to save others.

On June 1,

1968, the action shifted to the Plain of Reeds, a watery grassland forming a

triangle between the Vam Co Tay (Oriental) and Vam Co Dong (Occidental) Rivers

and the Cambodian border. The VC

and NVA used the area as an infiltration corridor and established rest and

resupply camps along the wooded riverbanks and several canals built by the

French to allow the area to be inhabited—it never was.

There enemy units were trying to regroup after the disasters that befell

them during the Tet Offensive. C

Company 2-39th Infantry was the first unit to air assault into the

vicinity of a suspected base camp. The

VC let the helicopters land, disembark the troops, and depart before they

struck. As the UH-1H “Hueys”

and AH-G “Cobra” gunships departed, the VC cut loose with everything they

had from a complex of bunkers concealed in bramble thickets and grass that was

up to 8 feet tall in places. Enemy

fire came from so close that there was no possibility of engaging the enemy with

artillery and helicopter gunships. The

best C Company could do is hug the earth in the tall grass, and hope the enemy

fire would pass harmlessly over their heads.

Many were not so lucky, cut down in the opening fusillade of fire.

A Company 2-39th

Infantry and two companies of 2-60th Infantry were lifted into the

area to relieve the pressure on C/2-39th. Each of the companies ran into more bunkers, precipitating a

succession of hot firefights at close range.

Where feasible, artillery and Cobra gunships from 7-1st Air

Cavalry were brought in to pound the area.

Despite the odds, the enemy slipped away during the night.

A sweep of the area in the morning revealed upward of 300 bunkers, 41

enemy dead, numerous weapons, and blood trails through the grass to the south.

To keep the pressure on Colonel Henry E. Emerson, the 1st

Brigade’s Commander, airlifted A Company 2-39th Infantry into an

area along a wooded canal where he suspected the enemy might have fled.

He was right. As A Company moved toward the treeline, it came under heavy

fire, killing its commander and several others.

Air strikes, gunships, and artillery pounded the area while Emerson

landed company after company into the surrounding area to box the enemy in.

A, B, and C Companies 2-60th Infantry, A and C Companies 2-39th

Infantry, and C Company 4-47th Infantry were inserted to form a tight

perimeter. A border ranger unit from Duc Hue Special Forces Camp covered

the canal’s opposite bank. In 4

days of hard fighting, 228 enemy soldiers and 36 Americans were killed.

It had been a lopsided but costly victory for the 1st Brigade.

On December 29,

1968, an ambush patrol sent out by B Company 2-39th Infantry ran into

a VC force on the move. After

routing the enemy, the patrol set up an ambush along a paddy dike, expecting the

enemy to return. They returned just

after midnight, throwing several grenades to mask their location.

One grenade wounded two Americans and a second landed near a cluster of 4

soldiers that included PFC David P. Nash. Instead

of rolling away to safety, Nash shouted a warning and jumped toward the grenade,

intending to throw it back. His

body took the full force of the explosion, killing him instantly, but saving the

lives of his comrades. He was

awarded the Medal of Honor for his selfless act of courage.

On January 6,

1969, A Company 2-39th Infantry again ran into trouble when it ran

into a bunker complex in Kien Phong Province.

Caught in a crossfire, the company became pinned down.

Staff Sergeant Don J. Jenkins grabbed a machinegun from its dead gunner

and crawled forward to try to relieve the pressure.

When the gun jammed, he grabbed a rifle and continued to fire into enemy

bunkers from an exposed position. When

another soldier cleared the machinegun’s stoppage, Jenkins fired the weapon

until it ran out of ammunition. Repeatedly

he crossed open ground to get more ammunition and return to the gun. When he was unable to find more ammunition, he collected two

antitank weapons and fired them into enemy bunkers from a distance of only 20

yards. Although wounded, he then

took up a 40mm grenade launcher and pumped round after round into other bunkers

within his field of vision, relieving the pressure on his sector.

Seeing that 3 wounded men were laying in the open under enemy fire, he

rushed forward again and again, dragging or carrying them to safety.

Jenkins’ inspirational leadership and repeated feats of courage rallied

his platoon and earned him the Medal of Honor.

Between January

and April 1969, the 9th Division was in almost constant combat,

working the paddies, canals, rivers, and swamps of the northern Delta, fertile

Long An Province, and the Plain of Reeds to thwart a third enemy attempt to

attack Saigon. Although exact

results are hard to determine in battles fought mostly in densely foliated

terrain or at night, but it is certain that the VC failed to invade Saigon

again. Estimated enemy casualties

ranged between 8000 and 9000, a disastrous blow to the VC who had already

suffered heavily the year before.

In June 1969,

it was announced that the 9th Infantry Division would be the first

unit withdrawn under President Nixon’s Vietnamization program, turning the war

in the Delta over to ARVN forces who had grown steadily stronger over the years

they had operated alongside the 9th. Elements of the division began departing in July and the

division was officially inactivated at Schofield Barracks, Hawaii on September

25, 1969. When it passed from the

active rolls, the 9th had served in combat on three continents, had

been in battle for nearly seven years, had earned 6 foreign awards, and its

members had earned 15 Medals of Honor (5 in World War II and 10 in Vietnam).

But not all of

the division was included in the inactivation.

As in 1918, part of the division remained active.

The 3d Brigade remained in Long An Province to shield Saigon’s southern

approaches. Its components included

the 6th Battalion 31st Infantry, 2d Battalion (Mechanized)

47th Infantry, 2d Battalion 60th Infantry, 5th

Battalion 60th Infantry, 2d Battalion 4th Field Artillery,

99th Support Battalion, D Troop (Air) 5th Cavalry, E

Company 75th Ranger Infantry, and the 118th Assault

Helicopter Company. The brigade’s

robust organization was also a test of a new separate brigade concept.

Because of the

intense fighting in the 9th’s area of responsibility in 1968 and

1968, things were fairly quiet in the northern Delta and Long An Province in

1970, but there were always an occasional encounter with an enemy squad or

platoon and constant encounters with booby traps to keep the “Go Devils” of

the 3d Brigade on their toes. Elements

of the brigade moved from Long An Province into the pineapple fields of Hau

Nghia Province on Saigon’s western approaches.

Throughout its remaining tour, the 3d Brigde operated under the control

of the US 25th Infantry Division, headquartered at the sprawling Cu

Chi base camp in the northwestern part of Hau Nghia. In April 1970, ARVN troops invaded enemy base areas in

Cambodia that had long been a safe haven for the Viet Cong. The offensive was prompted by a favorable change in

Cambodia’s government and the brutal slaughter of ethnic Vietnamese in several

Cambodian cities.

It was not long

before the 3d Brigade went into action in support of the Vietnamese, but it

would not fight as a brigade. 2-47th

Mechanized Infantry and 5-60th Infantry were detached to the 1st

Cavalry Division, which crossed the border from Tay Ninh Province to invade a

huge base area near the Snuol Rubber Plantation. 2-60th Infantry was detached to the US 25th

Infantry Division in its drive along the long-closed Highway 1 linking the

Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh with Saigon.

Only 6-31st Infantry remained under 3d Brigade control,

attacking across the Plain of Reeds to seize the Ba Thu base area and pursue

retreating enemy units toward the Cambodian Provincial capital of Svay Rieng.

In a series of sharp firefights in and around towns with nearly

unpronounceable names, the “Polar Bears”[16]

of the 6-31st acquitted themselves well, pushing to within a few

miles of Svay Rieng before President Nixon announced for political reasons that

no American troops would advance more than 21.7 miles into Cambodia.

We were already at the limit and in some cases just beyond.[17]

[17]

On his second tour in Vietnam, the author served with 6-31st Infantry

during the period described.

At Chantrea, a

district capital, Companies A, B, and D of the Polar Bear battalion engaged an

enemy battalion dug into the town. Each

company took losses as it landed and attempted to rush the woodline defining the

town’s straight edges. Each

landing was met with 81mm mortar, RPG, and .51 caliber heavy machinegun fire,

added to intense 7.62mm machinegun and automatic rifle fire. At least one helicopter was lost on the landing zone and

several others were severely damaged, but the tough UH-1 “Huey” assault

helicopters continued delivering riflemen into fire-swept landing zones,

oblivious to the risks involved.

After 3 days

and 2 nights of constant see-saw battles, countless attack helicopter and air

strikes, and so heavy a pounding by artillery that C Battery 2-4th FA

ran out of ammunition, the battlefield became quiet.

By the morning of May 10, 159 enemy soldiers lay dead in the open, in

bunkers, or in destroyed buildings throughout the city.

Six “Polar Bear” soldiers had been killed, all on the battle’s

first day. The battle was over in

Chantrea but some of the enemy battalion had slipped out to the west.

D Company pursued the survivors to nearby Thnaot where another day-long

battle ensued.

Fighting at

close quarters amid a previously prepared network of bunkers and trenches

arrayed in depth throughout the town, D Company’s 2d and 3d Platoons fought

tenaciously. Their assault,

conducted beyond the range of supporting artillery, quickly got inside the

enemy’s minimum mortar range and began taking apart the enemy’s defenses by

clearing out one cluster of 6-8 interlocking bunkers at a time.

Rifles, rockets, and grenades flew back and forth in nearly every

courtyard and open space in the town’s southern and eastern quadrants and the

company pressed its attack. Specialist Dennis K. Walker and PFC Daniel Wood each earned

the Distinguished Service Cross for their determined and successful two-man

rifle and hand grenade assault to rescue a pinned down squad.

Five other members of the company earned the Silver Star that day (two

posthumously) for acts of courage in destroying a numerically superior force in

prepared positions. In late afternoon, a spread of folding fin aerial rockets

delivered by a pair of Cobra gunships, followed by a napalm strike by an Air

Force F-4C Phantom knocked out the enemy’s remaining heavy weapons but

sporadic fighting continued into the night.

Rather than continue the fight another day, the enemy withdrew to the

northwest around midnight, covering its withdrawal with a final weak outburst of

green tracers and RPGs splitting the darkness all along the line.

On May 12,

President Nixon, again appeasing vocal political opposition, announced that he

was withdrawing 2 US divisions from the fighting in Cambodia—the 4th

and 9th Infantry Divisions. It

was probably clear to no one that the 9th’s withdrawal amounted to

only a single battalion task force. Other battalions of the 3d Brigade remained in Cambodia for

another month or more with the 1st Cavalry and 25th

Infantry Divisions.

After the

Cambodia campaign, sporadic firefights resumed in Long An and Hau Nghia

Provinces as VC elements tried to resurrect their shattered political and

military infrastructure. In

October, it was announced that the rest of the 9th Infantry Division

was going home. The 3d Brigade

turned over its bases to the ARVN 25th Division and assembled at Di

An, the old 1st Infantry Division base camp, for departure.

Many members who had not yet completed their full year-long tour of duty

would be sent to other divisions throughout Vietnam, but the colors would go to

Ft Lewis, Washington for inactivation on October 13, 1970.

For the first time in 4 years, there were no longer any active units

wearing the octofoil patch.

General Creighton Abrams, appointed the Army’s

Chief of Staff after the war, set out to rebuild the Army from its post-war low

of 13 divisions and make it ready again to fight if called on.

The first division he reactivated was the 9th Infantry

Division, unfurling its colors at Ft Lewis on April 21, 1972.

The division’s maneuver structure was initially more conventional than

when it went to Vietnam in 1967. Because

the traditional hosts of some of the Army’s oldest regiments were no longer

active, battalions of the 1st and 2d Infantry and 77th

Armor replaced the 4th Battalions of the 39th and 47th

Infantry and the 5th Battalion 60th Infantry.

6-31st Infantry was reactivated as part of the 7th

Infantry Division at Ft Ord the following year and later moved to Ft Irwin,

California where it became the infantry component of the National Training

Center’s Opposing Force. Most

other elements of the division were initially the same as those that had served

with the division in Vietnam.

General Creighton Abrams, appointed the Army’s

Chief of Staff after the war, set out to rebuild the Army from its post-war low

of 13 divisions and make it ready again to fight if called on.

The first division he reactivated was the 9th Infantry

Division, unfurling its colors at Ft Lewis on April 21, 1972.

The division’s maneuver structure was initially more conventional than

when it went to Vietnam in 1967. Because

the traditional hosts of some of the Army’s oldest regiments were no longer

active, battalions of the 1st and 2d Infantry and 77th

Armor replaced the 4th Battalions of the 39th and 47th

Infantry and the 5th Battalion 60th Infantry.

6-31st Infantry was reactivated as part of the 7th

Infantry Division at Ft Ord the following year and later moved to Ft Irwin,

California where it became the infantry component of the National Training

Center’s Opposing Force. Most

other elements of the division were initially the same as those that had served

with the division in Vietnam.

In

1982, the 9th Division was converted from a standard infantry

division to an operational test bed or field laboratory to explore new

equipment, tactics, and organizations. Funding

problems hobbled the effort from the start.

Although the Army Staff was able to overcome some of the resulting

acquisition problems, legal obstacles to off-the-shelf acquisition limited the

division’s usefulness as a test bed. Moreover,

the division was a hybrid that no single branch school would champion as its

own, leading to lower priority status. By

1988, budget cuts forced the elimination of the division’s 2d Brigade.

In its place the 9th incorporated the Washington National

Guard’s 81st Mechanized Infantry Brigade.

The reorganization gave the division 2 light infantry battalions, 2

mechanized infantry battalions, three tank battalions, and four motorized

combined arms battalions (each with 2 rifle companies and an antitank company).

Although aspects of the new structure would shape the thinking of a

future generation of leaders, the division lasted only 3 more years.

It was inactivated at Ft Lewis on December 15, 1991.

World War II

Vietnam

Algeria-French Morocco

Counteroffensive, Phase II

Tunisia

Counteroffensive, Phase III

Sicily

Tet Counteroffensive

Normandy

Counteroffensive, Phase IV

Northern France

Counteroffensive, Phase V

Rhineland

Counteroffensive, Phase VI

Ardennes-Alsace

Tet 1969 Counteroffensive

Central Europe

Summer-Fall 1969

Winter-Spring 1969 (3d Brigade only)

Winter-Spring 1970 (3d Brigade only)

Sanctuary Counteroffensive (3d Brigade

only)

Counteroffensive, Phase VII (3d Brigade only)

Decorations (shown

only to brigade level):

Belgian Fourragere

Belgian Army Order of the Day for action at the Meuse River

Belgian Army Order of the Day for action in the Ardennes

Republic of Vietnam Cross of Gallantry with Palm 1966-1968

Republic of Vietnam Cross of Gallantry with Palm 1969

Republic of Vietnam Civil Action Honor Medal 1st Class 1966-1969

Presidential Unit Citation DINH THUONG PROVINCE (1st Bde only)

Presidential Unit Citation MEKONG DELTA (2d Bde only)

Valorous Unit Award BEN TRE (3d Bde only)

Valorous Unit Award SAIGON (3d Bde only)

Medals of Honor (** indicates posthumous

awards):

World War II:

·

Herschel F. Briles**, C Co

899th Tk Dest Bn

·

2LT John E Butts, E Co 2d Bn

60th Inf, near Cherbourg, France, 19 Jun 1944

·

T/Sgt Peter J. Dellesondro,

E Co 2d Bn 39th Inf, near Monschau, Germany, 22 Dec 1944

·

William L. Nelson**, 60th

Inf,

·

Carl V. Sheridan**, K Co, 3d

Bn 47th Inf, near Aachen, Germany, 26 Nov 1944

·

LTC Matt Urban, HQ 2d Bn 60th

Inf, Normandy, France, 17 Jun 1944

Vietnam:

·

SGT Sammy L. Davis, C Btry

2d Bn 4th FA, near Cai Lay, Dinh Thuong Province,18 Nov 1967

·

SP4 Edward A. Devore**, B Co

4th Bn 47th Inf, Gia Dinh Province, 17 Mar 1968

·

PFC James W. Fous**, E Co 4th

Bn 47th Inf, Kien Hoa Province, 14 May 1968

·

SSG Don J. Jenkins, A Co 2d

Bn 39th Inf, Kien Phong Province, 6 Jan 1969

·

SGT Leonard B. Keller, A Co

3d Bn 60th Inf, Ap Bac, Long An Province, 2 May 1967

·

SP4 Thomas J. Kinsman, B Co

3d Bn 60th Inf, Vinh Long, Vinh Binh Province, 6 Feb 1968

·

SP4 George C. Lang, A Co 4th

Bn 47th Inf, Kien Hoa Province, 22 Feb 1969

·

PFC David P. Nash**, B

Co 2d Bn 39th Inf, Giao Duc, Dinh Thuong Province, 29 Dec 1968

·

PFC Clarence E. Sasser, HHC

3d Bn 60th Inf, Dinh Thuong Province, 10 Jan 1968

·

SP4 Raymond R. Wright, A Co

3d Bn 60th Inf, Ap Bac, Long An Province, 2 May 1967

9th

Infantry Division Duty Stations:

·

1918-1919

Cp Sheridan, Alabama

·

1940-1942

Ft Bragg, North Carolina; Ft Dix, New Jersey

·

1942-43

French Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Sicily (Combat Service)

·

1943-44

England

·

1944-45

France, Belgium, Germany (Combat Service)

·

1945-47

Germany (Occupation)

·

1947-54

Ft Dix, New Jersey

·

1954-56

Germany (Occupation and NATO Service)

·

1956-62

Ft Carson, Colorado

·

1966

Ft Riley, Kansas

·

1967-70

Vietnam (Combat Service)

·

1972-91

Ft Lewis, Washington

Temporary Wartime Attachments:

World War II:

·

746th Tank Battalion

13 Jun 1944-10 Jul 1945

·

629th Tank Destroyer

Battalion

16-25 Aug 1944)

·

899th Tank Destroyer

Battalion

19 Jun-24 Jul 1944

·

376th AAA Automatic

Weapons Battalion

13 Jun 1944-26 May 1945

·

413th AAA Gun Battalion

20 Dec 1945-3 Jan 1945

Vietnam:

·

H Battery 29th Artillery

(Searchlight)

24 Mar 1967-1 Jun 1969

·

6th Battalion 77th

Field Artillery (105mm)

20 Jul 1968-15 Jul 1969

·

214th Combat Aviation

Battalion

15 Jan 1967-15 Jul 1969

·

39th Cavalry Platoon

(Air Cushion Vehicle)

1 May 1968-30 Sep 1970

·

1st Battalion 16th

Infantry

1-31 Oct 1968

·

E Company 50th Infantry

(Long Range Patrol)

20 Dec 1967-1 Feb 1969

·

E Company 75th Infantry

(Ranger)

1 Feb 1969-12 Oct 1970

·

43d Infantry Platoon (Scout Dog)

19 Aug 1967-1 Jun 1969

·

45th Infantry Platoon

(Scout Dog)

19 Aug 1967-12 Oct 1970

·

65th Infantry Platoon

(Combat Tracker)

15 Feb 1968-15 Jul 1969

·

335th Army Security

Agency Company

12 Jan 1967-31 Jul 1969

NOTE: Many other units supported the 9th Infantry Division in combat, but were neither attached nor assigned to the division. The above listing reflects only those units that were officially attached.

Return to the SONID Main Page

Return to the 15th Engineer Main Page - only for those visiting from the 15th Engineer Web Site (do not select if you came from the SONID Main Page)

For SONID visitors who wish to visit the 15th Engineer Web Site please select 15th Engineers